For a few months before arriving at Gladstone’s Library I had been trawling through the London Illustrated News online archive in the British Library’s reading rooms at St Pancras. Published on a Saturday from 1844 onwards, the ILN featured evocative woodcuts of the image of the week, and hunting through their archive you could find wonderful depictions of famous Victoriana like the Great Exhibition or SS Great Eastern, the first wooden telegraph hut in Slough or John Welsh’s intrepid balloon ascents. All these lay at the far side of a search box. Simple. Click. Click.

And then it was the start of March and I was off to Gladstone’s Library – which was described so aptly by Peter Francis this morning (you can find a link to this here) on Radio 4 as ‘a health spa for the mind.’ I’d bargained for the books but what I had not anticipated was the nineteenth century journals and magazines. I spotted them on my first tour of the library within about ten minutes of arriving. There was a set of (almost) complete London Illustrated News volumes nestled at the end of the annex. Opposite them were a row of red leather- bound Punches, nearby was the Strand Magazine (of Sherlock fame) and all around there were different reviews, quarterlies and encyclopaedias.

But it was the ILN that I was after, and I got started on them the very next morning.

When historians look back on these early years of the digital revolution they will probably write long books about the sudden and bewildering democratisation of information. For example, over the last decade an Elphel 323 camera has been ticking away in an anonymous US office block, a little heartbeat, capturing page after page of old publications for the Google Books project. The Elphel Camera runs at one thousand pages an hour. That’s Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield in fifty minutes, the King James Bible in half an hour, Animal Farm in ten minutes or The Communist Manifesto in five.

Google Books have now processed thirty million items – books, pamphlets, chapbooks, magazines – and there’s no sign of them letting up yet. Keyword searchable, it means that relevant content flies to the top of results pages like iron filings to a magnet. And Google Books is just the tip of the iceberg. There’s the British Library Sound Archive with a million discs and 185,000 tapes of accents, soundscapes and so on, the BBC Archive, the full Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. These are just a tiny part of what is available to the everyday Internet user – a true Library of Alexandria at the click of a mouse.

Like any other writer I’ve benefitted from this avalanche of easily discovered, highly-relevant content. You can fly at it like a harpoon. Find facts in minutes that might have taken hours or days just a few years ago.

But in the ponderous silence of the history room at Gladstone’s Library, flicking through one volume of ILN and Punch after another, I forgot about digital archives for a while and rediscovered the benefit of browsing slowly, from issue to issue.

It is difficult to do this at a computer screen. Results are always returned in isolation from the page they appeared on. They tend to look like clipped columns, like you might find in an old scrapbook. If you are given the choice to view an entire page of text it’s useful. But remember that the average nineteenth century broadsheet had the wing span of a red-kite. To try and look at one page in full is tricky and to browse a whole issue on a computer is a logistic nightmare.

Not so if you’ve got the original issue in your hands or on your desk. And this is exactly what you can do at Gladstone’s Library. It changed my research. I read issue after issue, week after week, month after month. I could pick up the recurring themes and characters in Punch: the mischievous Italian, the slippery Disraeli and irascible Gladstone. I could follow the ILN and their obsession with chess and their relish for new technology like the telegraph. You could see stories develop organically. Rather than researching something in isolation you could see it in context, finding all of those beautiful, incidental details that a book thrives on.

In my month at Hawarden I got through the ILN from its launch in 1844 to the mid-1860s and Punch for about the same period. I came home with a journal full of notes and ideas – stories, anecdotes, plot-lines.

So of the many reasons to visit Gladstone’s Library – the quiet, the environment, the magic, the history, the beauty – here is another. It has one of the best stores of nineteenth century journals and newspapers you can imagine and it gives you the time and the space to research them in ways that digital archive can’t hope to emulate.

I’ll finish off with a few photographs of my favourite woodcuts from the ILN.

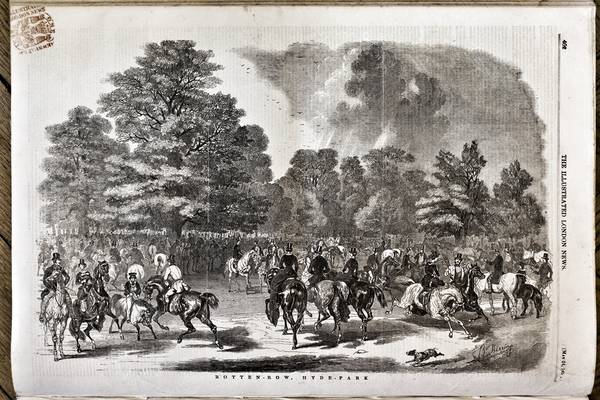

Rotten Row Hyde Park

High quality photograph of a woodcut form the Illustrated London News, featuring Hyde Park

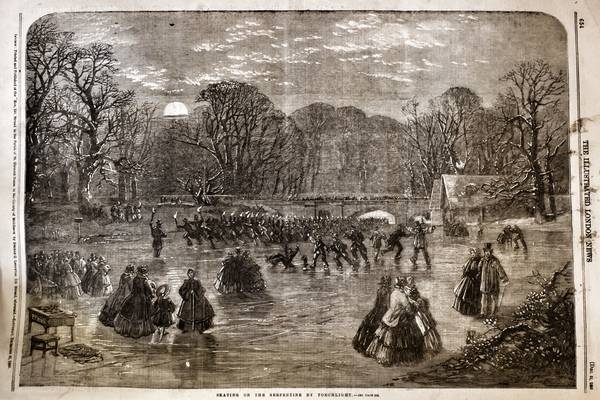

Skating on the Serpentine by Torch-Light

A woodcut from the Illustrated London News of ice skaters on the Serpentine

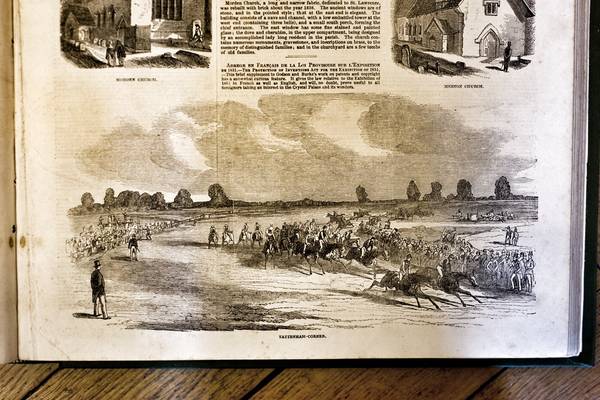

Tattenham Corner

A woodcut of Tattenham Corner from the Illustrated London News

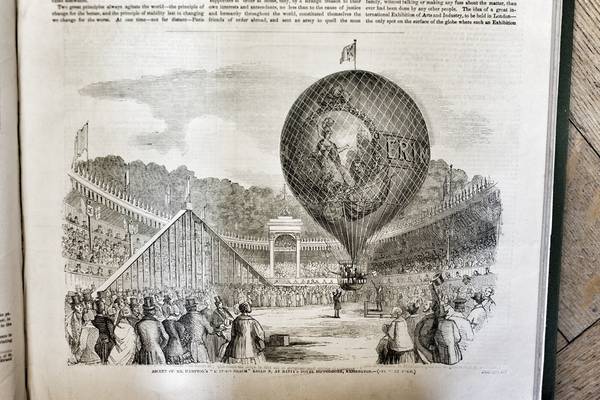

Ascent of Mr Hampton’s Balloon from Kennington

A woodcut showing the triumphant rise of Mr Hampton’s Balloon from the Illustrated London News