The title is certainly intriguing. Intriguing too is the fact that Gladstone clearly read this autobiography (the author remains anonymous) carefully, as attested by his many pencil written annotations. One can indeed be surprised at a political figure such as Gladstone being interested in the life of a nun, but it must not be forgotten that Gladstone was a religious man and a fervent advocate of Anglicanism. Thus it is likely that his interest in this book was not so much the life of a nun as her move from Protestantism to Catholicism and the comparisons between the two it entails.

This is not an austere and dull book. It is full of lively anecdotes and remarks, windows on a time long gone, more precisely 1869 when the book was written. For example, one learns with some amazement that a preacher would not hear a married woman’s confession “unless she had first obtained permission from her husband;” amazing too are remarks like “I had always believed, as most Protestants do believe, that priests and monks were very wicked people …” and “The bishop of the diocese strongly disapproved of prayers for the dead …”

Whilst taking us back in time, this book shows us, at the same time, that the human mind has not changed much. The author recounts that when she made her intention to become Catholic known, she encountered a wall of suspicion and opposition, discovering in the process that her friends were few. Prejudices and preconceived ideas are far from disappearing in our time; take Ireland and the still fragile reconciliation between its two communities, or a subject like the place of Britain in Europe, which too often provokes if not conflicts, bad feelings between opposing parties.

The comparison between Protestant and Catholic beliefs that this book offers is also interesting, because it is still relevant nowadays even though this comparison is based in part on the author’s personal experience, and consequently, distorts its validity. The negative experience the author suffered in the Protestant sisterhood was essentially due to the flaws of the woman who stood as its Superior. Unfortunately, the abuse of power the author found in the sisterhood also exists in some Catholic convents, in the same way, I presume, that the kindness and generosity of heart she found in a convent is also present in a Protestant community.

However, the real beauty of this book is the truthfulness of the author’s spiritual search and its relevance to us. “Was this Babel of religious opinion, in which few seemed to agree … the religion which the Son of God had come to teach the world?” she asks. “Had a God of love left His last testament to be a source of discord instead of a declaration of His will? Her questions are clearly those of a wise and intelligent woman and just as relevant today as they were in her time.

There are, however, questions which the author could not ask because they, somehow, only belong to our time such as: can we judge the value of a religion by its followers? Is it necessary to belong to a church to find God? I doubt Gladstone would have asked the last question, but in the end, that is the one this book left me with.

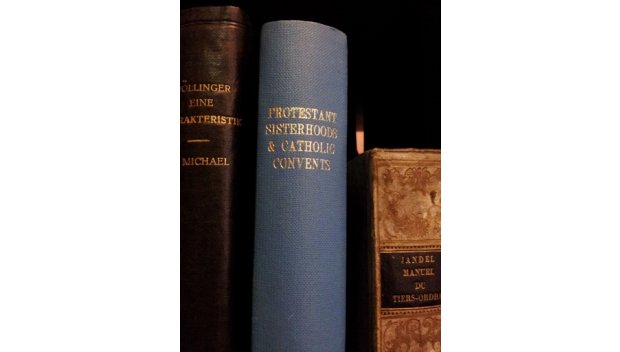

Five Years in a Protestant Sisterhood & Ten Years in a Catholic Convent can be found in the History Room at Gladstone’s Library.

Muriel Maufroy is a volunteer at Gladstone’s Library. Muriel’s personal blog can be found here.