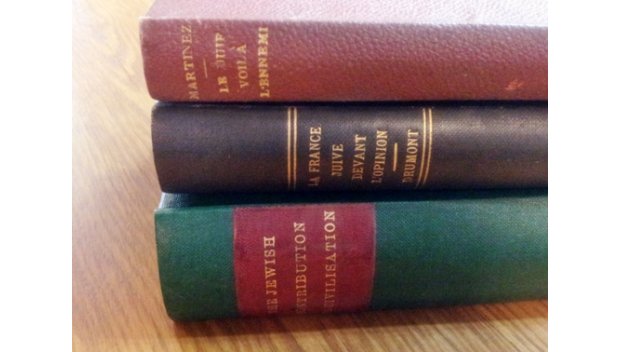

That different people may at times hold completely opposite opinions on a specific subject, appealing in both cases to large audiences, is strikingly evident to anyone browsing through the shelves of Gladstone’s Library. On the subject of Judaism, it comes as a shock to find next to each other a book like The Jewish Contribution to Civilization by Cecil Roth, published in 1938, and a work in three volumes, La France Juive (Jewish France) by the violently anti-semite, Edouard Drumont, published more or less at the same time. Clearly, this last work does not aim to inform, but to defend a set of beliefs, and rather than resorting to facts, resorts to half truths and their emotional impact on the reader. In the same vein and equally in French, is Le Juif, Voila l’Ennemi (The Jew, Here is the Enemy) written by a certain Dr Martinez, Professor of Theology (no less), and published much earlier -in 1890, but just as poisonous in its stands.

These last two books strangely echo the attitudes and opinions held today towards Islam. Replace the word ‘Jews’ with the word ‘Muslims’ and you realize that nothing much has changed when it comes to prejudices, distortion of the truth, and the feeding of the most ingrained human fears. ‘The Jew,’ Dr Martinez asserts, ‘is the enemy of the Catholic religion.’ His proof: the report of an interview with a Jew who confessed to the killing of a priest to use his blood in a Jewish ritual. Significantly, the author remains quite vague as to how the man came to make his confession.

Rather than dealing in mud, let’s look at the work of Cecil Roth in The Jewish Contribution to Civilization. Roth notes that, in the nineteenth century, the Jewish people were scattered throughout the world; ‘They had been in Spain as early as the beginning of the Christian era. They were to be found in France from the first century onwards. Inscriptions and literary evidence attest their presence in Hungary, in the Balkans and in South Russia, until they disperse in the new centres on the Atlantic seaboard.’ he remarks, ‘Deprive modern Europe and America of the Hebraic heritage, and the result would be barely recognizable. It would be a different and it would be a poorer thing.’ These are facts we more or less know. What is less known is the fact that, during the first half of their history, the Jews had been ‘rooted on the soil, with a solid basis of peasant proprietors. Trade was in the hands of non-Israelites traders.’ A fact mostly ignored, which goes against a classic assumption concerning the ascendency of the Jews over international trade and finance, If the Jews became involved in finance, explained the author, it is due ‘to the frequency of persecution which, time after time, uprooted the Jewish agriculturalist from his previous home and drove him into a strange country where there was no room for him on the soil.’ Roth also notes that the quasi-hegemony of the Jews in banking during the nineteenth century was disrupted by the outbreak of the First World War. ‘Nowhere today does the influence of the Jew even approach a financial monopoly.’ The author also remarks that ‘it is too often overlooked that the vision and courage of the financial magnate – Jewish or not – is frequently responsible for achievements of enormous benefit to the public’ as well as for ‘his power in deciding War. Less is said about his power in deciding Peace.’

A typical aspect of prejudice and truth distortion is exemplified in the famous Waterloo Fable, recounted by Roth. Apparently, in order to deceive the Stock Exchange, Nathan Meyer Rothschild followed Wellington to the field of Waterloo then sent a dispatch to London hinting at disaster while secretly buying the depressed stock and thus, earning for himself several millions of pounds. The truth is that Nathan Rothschild had remained in London and never went to Waterloo. He had effectively learned of the result of the battle before anyone else through his own news service, but far from keeping it for himself, hinting at disaster or profiting by it, ‘he immediately communicated the news to the Prime Minister who actually refused to believe him.’ Far from depressing the market by suggesting there had been a British disaster, ‘the truth is that he had bought openly and largely, in the face of an incredulous and falling market.’ Such is the power of prejudices that the story continues to this day to be told.

The book contains many stories in the same vein. They show how the numerous achievements of the Jews have so often been denied and how the Jews have been again and again wrongly accused of the worse possible deeds. At the same time, Roth does not pretend that the Jews are without faults. He simply states that their contribution to the development of trade has been particularly important and needs to be acknowledged. In short, though published more than seventy years ago, this book is – unfortunately – still relevant and more than worth reading at a time when racial and religious prejudices are far from gone.

The books discussed in this blog post can be found at Gladstone’s Library.

Muriel Maufroy is a volunteer at Gladstone’s Library. Muriel’s personal blog can be found here.