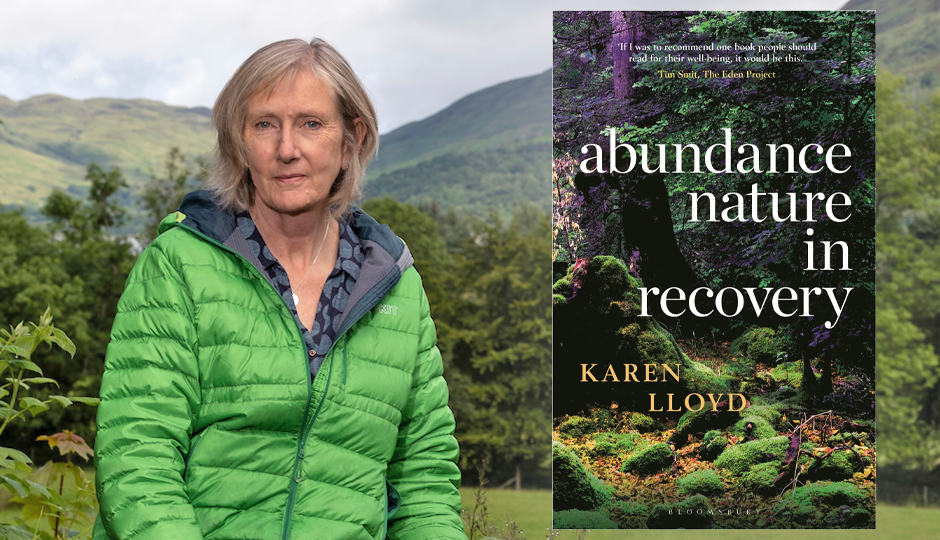

A Blog by Karen Lloyd, 2025 Writer in Residence at Gladstone’s Library and author of Abundance

The truth is, there’s no-one else to do this for you. You show up at your desk, or your laptop, or your notebook and pen, or your dream head, and you live in constant fear that the words themselves will fail to show up: that what you’d thought of as a partnership, or a tacit agreement that the words will quite reasonably stick to their side of the bargain, is only ever provisional.

And it’s not just about words. There has to be an inciting idea – what are you writing about and why? Paul Kingsnorth has it like this, ‘Something made me write this. Something called it into being. Words don’t just drop out of the sky, they have to be formed, and books too. Books are like people: they come from somewhere and they have to belong somewhere and they want something, but you don’t always know what it is.’

And then there’s all those plates to keep spinning – narrative drive, world building, voice and tone, imagery. If we think about voice, then it’s a case not only of what you want to say but how you want to say it. Over the years I’ve aimed for the voice of a fallible, self-deprecating narrator, because in all honesty there’s always so much I don’t know, and without due attention to the research of others – scientists, marine experts, ecologists etc – for a nature and environmental writer like me, there would be a lot less to write about. So how do I show that in the writing? Partly at least, it’s by acknowledging how much I simply don’t know. I’m also mindful of the need to process that information in a way that’s accessible for all the other non-experts out there too.

Then there’s the problem of language itself and the kinds of choices we make around imagery, metaphor and simile. Q. what is a cliché?, I ask my students. A. A simile is anything you’ve ever heard before. Despite this, in the writing workshop, those clichés pile up like sudden dumps of snow. But even here, let’s agree that sometimes a cliché is exactly what’s needed; if the sea does indeed sparkle, why should we not say so?

The late Clive James wrote about successful writing as writing that contains the ‘lightning strike of an idea’ that ‘goes beyond thought and perception and into the area of metaphorical transformation.’ James is writing here about poetry and about what ‘a poem demands,’ although as a writer mainly of non-fiction I also think frequently about exactly what the writing demands. It is not my intention to burden the writing nor the reader, to cause a six-mile tailback of adjectives and similes and metaphor and slow everything down to a crawl. Rather, what I intend is to create narrative as a kind of ‘viewing station’ from which world and word cohere, a place I can walk home from at the end of the day and look back (metaphorically) at the places I’ve been during those hours of writing and think quietly to myself, that’ll do.

I have a slide in one of my lectures where I talk about the writer Elizabeth Tallent, and how as a young trainee archaeologist she had the gradual realisation that in describing the skull of a Pleistocene antelope, she actually fell in love with writing, how she loved the written skull more than the actual one being gradually exposed to the light, how at night she wrote away, trying to get at the truth of the eye socket that had,10,000 years previously, been the eye of the living beast. Whenever I re-read this, I think, this it exactly. The eye – my eye – takes in the world and then the writing wants what it wants, which is to make sense of that observed world (external world, internal world) its uncanny habits, its chancy encounters. And let’s agree that just because you’re a writer of non-fiction there is still a world to build, because of course the world as witnessed has to be part of the bargain, mediated by writer and writing.

Constantly, I am led by the writing to destinations previously unknown, places that were unimagined when I’d sat at my desk that morning. Coming back to Kingsnorth, we may not always know what the writing wants, but the only way to find out is to keep going. Being at Gladstone’s Library for the second part of my residency is a case in point. Being here, showing up to the desk each day and putting everything together, research notes together with all those writerly concerns, a chapter begins to take shape and the writing begins to communicate what it needs. It is like setting out on a journey into a network of desire lines, even though there may only be a vague sense at this stage of where it will all conclude.

***

In late October I had the pleasure of leading a day of writing about nature and the environment here at Gladstone’s Library with a group of writers, a day in which a generous exchange of knowledge about the natural world manifest in a shared sense of wonder, and an opportunity to enjoy transposing that shared learning into the luxury of experimentation. The day was peppered with conversations about birds and landscapes and experiences, and there’d even been a gathering (a community, a population?) of Fly Agaric on the front lawn, which afforded us all a brilliant, transitory opportunity to think about natural processes and time, and how those convergences might eventually be shaped into words.