History is littered with bitter rivalries – Sparta and Athens, Lancaster and York, Tom and Jerry. But in recent centuries few have come close to matching the antagonism and divergence in styles that existed between two of Britain’s most significant leaders of the Victorian period, William Gladstone and Benjamin Disraeli. And what better way to learn about their rivalry than with the aid of every history student’s favourite source, (mostly because it beats sifting through mountains of unrelated papers), the satirical cartoon.

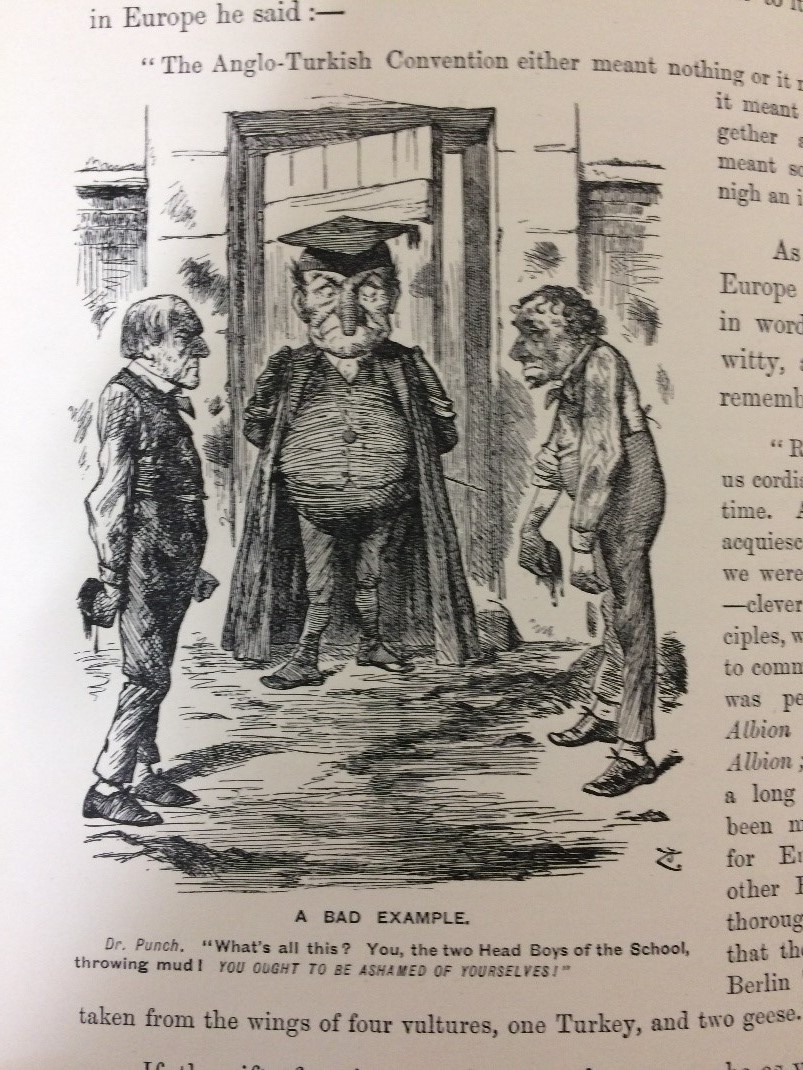

The rivalry began in 1846 with the split over the corn laws and it is easy to see how and why it grew. When Gladstone took over from Disraeli as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1852 he refused to pay his counterpart’s moving bill, as was the custom. In turn, Disraeli took with him the ceremonial gown usually worn by the Chancellor, denying Gladstone the chance to wear it. This point scoring continued throughout their careers and if all this all sounds rather childish, well, that’s because it was. This cartoon from Punch Magazine encapsulates their juvenility:

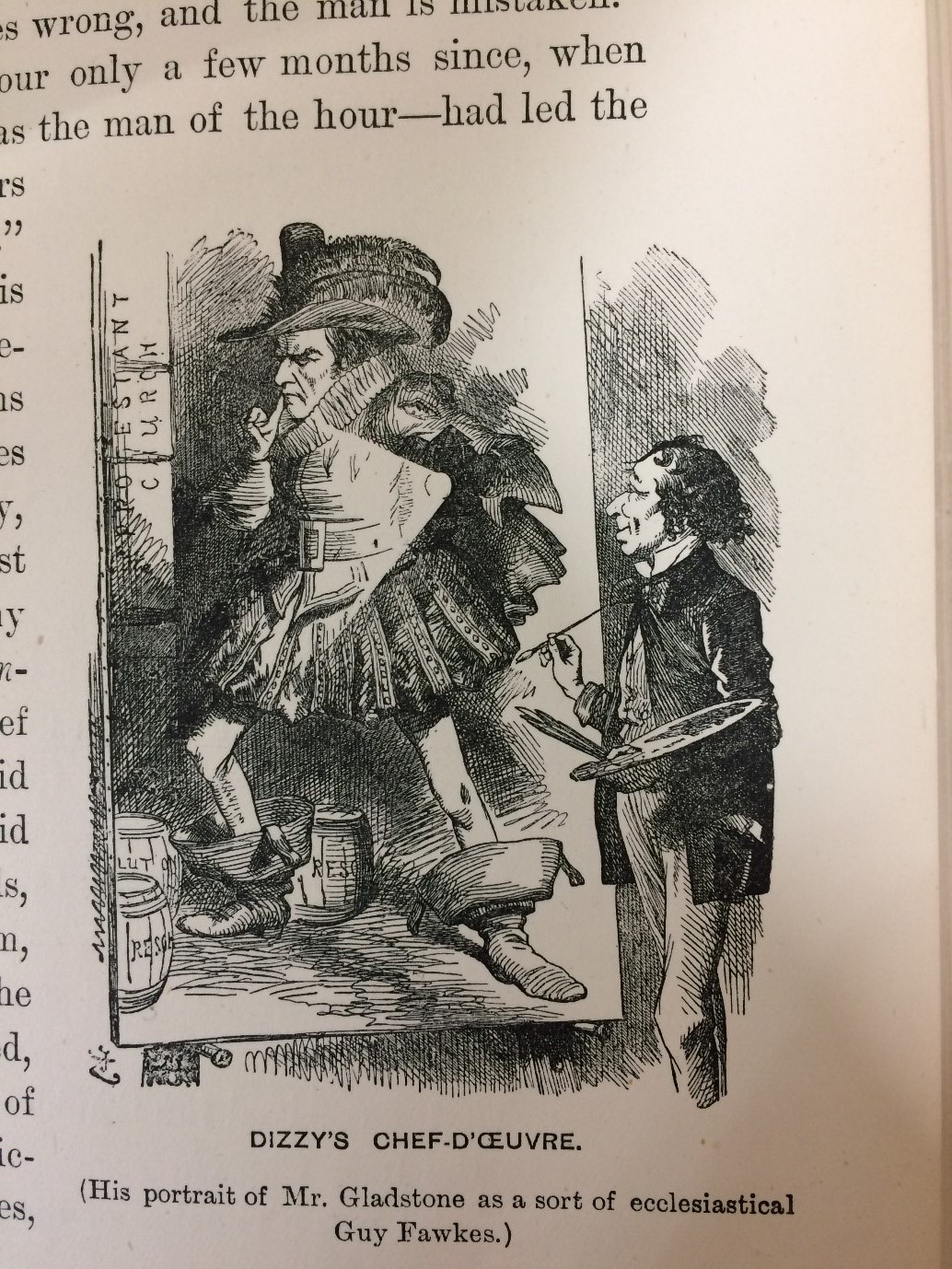

It wasn’t only political differences that divided the two – their oratory styles and personalities were also chalk and cheese. Gladstone was famously serious, sometimes coming across as ‘preachy’, and guided by his strict moral compass. Disraeli, on the other hand, often regarded as more of a pragmatist, was famous for his vibrant and witty oratory style. Disraeli was also prone to flattery. Winston Churchill’s mother, Jennie Jerome, famously wrote that after sitting next to Gladstone ‘I thought he was the cleverest man in England. But when I sat next to Disraeli I thought I was the cleverest woman’.

This cartoon points to Disraeli’s incredible talent for painting a certain picture with his language; in this case, as in most, that Gladstone was up to no good!

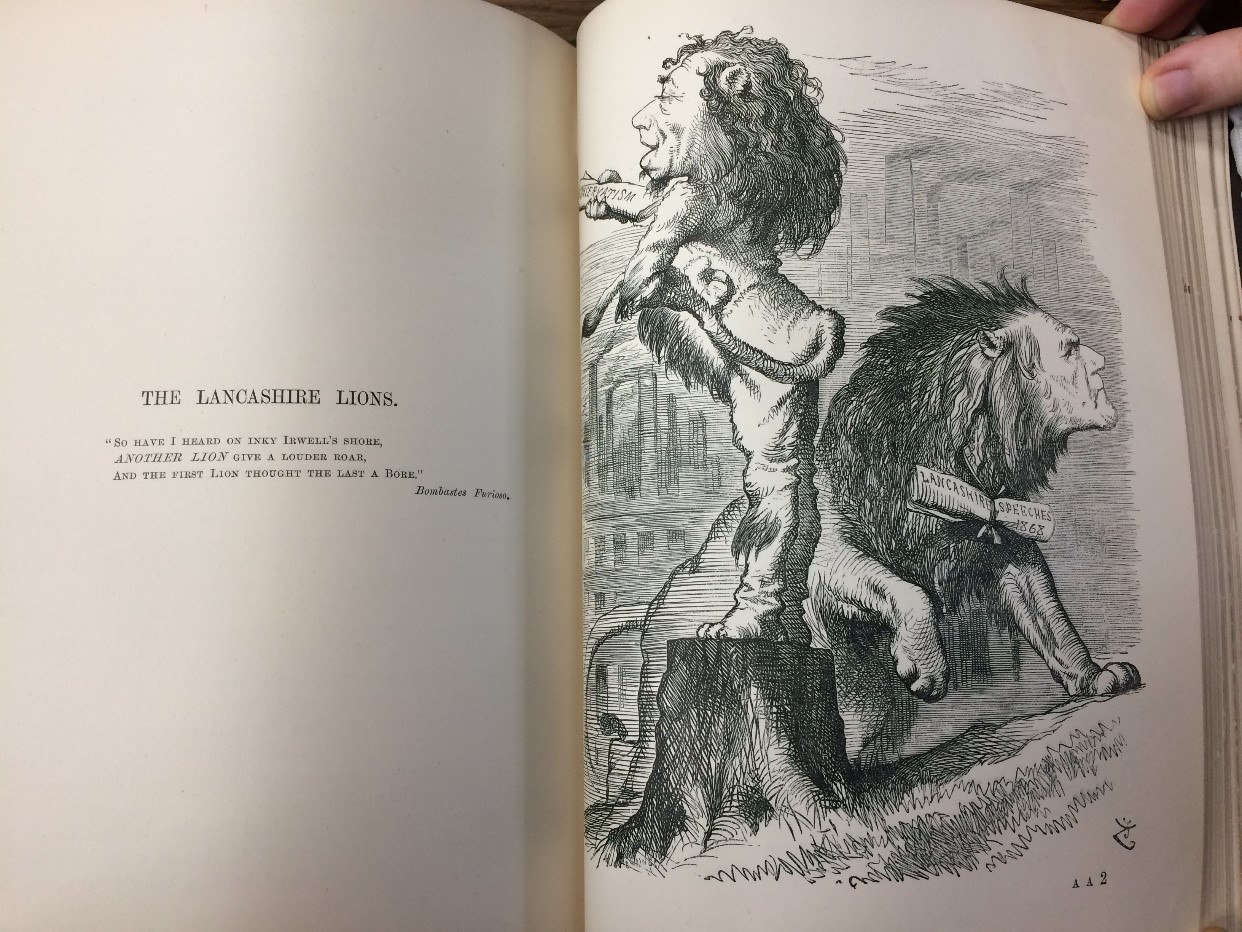

Gladstone may not have possessed the charisma of Disraeli, or his oratorical flair – Queen Victoria said ‘he speaks to me as if I were a public meeting’ – but he had other qualities. While Disraeli was seen in some quarters as a political adventurer, believing in nothing in particular, Gladstone was perceived to be a man who would stand up for what he believed regardless of public opinion. The British public were, on the whole, appreciative of Gladstone’s brand of politics and dubbed him ‘the People’s William’. However, the British people could only follow Gladstone’s high-minded morality so far. In 1872 he introduced legislation restricting the opening hours of the one thing that Brits hold most dear… the pub. He lost the next election, claiming he had been ‘borne down in a torrent of gin and beer’. Despite this set back, Gladstone continued to receive massive support and went on to become Prime Minister a further two times.

As this cartoon shows, Gladstone was well respected for the strength of his beliefs, in stark contrast to Disraeli who was in some instances ridiculed for a lack of courage in his convictions:

It is amazing to think that neither Gladstone nor Disraeli, who are considered two of the greatest politicians in British history, were ever politically dominant for long periods. Between them they held the office of Prime Minister six times and yet neither ever won consecutive elections. This was largely the result of their rivalry. Whilst they were polar opposites, each appealed to different aspects of the nation’s psyche. As a result, as the public’s attitudes and opinions shifted, so did the balance of power meaning neither ever truly gained the upper hand. Even Disraeli’s death failed to temper Gladstone’s feeling towards him. Gladstone had offered him a state funeral and burial in Westminster Abbey however Disraeli left instructions for a more modest service. This lead Gladstone to write, ‘As he lived, so he died – all display, without reality or genuineness’.

By Henry Cutts, Intern