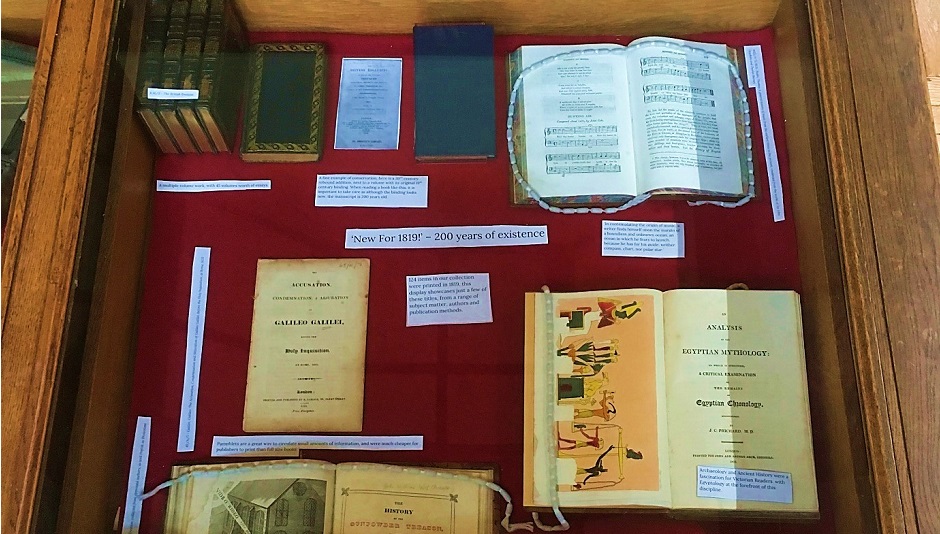

At Gladstone’s Library we rotate our History Room display every month to focus on a different aspect of our collection. This month we’ve dug out some of our best examples of works published in 1819, exactly 200 years ago, to give you a taste of what people were reading during the Georgian Regency period of British history.

1819 was an explosive year in Britain and for Britain’s influence around the world. In January Sir Stamford Raffles landed on the island of Singapore, originating 150 years of British colonial territory on the island. In July, the Prince of Wales’ wife was very nearly charged with adultery due to reports that she was involved with one of her servants, although it was deemed that a trial would be an embarrassment not only to the Prince of Wales (who was Regent at the time and would become King as George IV in 1820), but for the nation as a whole and so it was decided against. Both the future Queen Victoria and her consort Prince Albert were born in 1819 – while in August, a cavalry charge against protesters at Manchester resulted in 15 deaths and approximately 600 injuries, becoming infamous as the Peterloo Massacre, a glaring example of government oppression.

Regarding books in 1819, the literacy rate in Britain was still low. While more people could read than write, books were still expensive and had not yet benefitted from either the cheaper printing costs of industrialisation or the efforts of novelists like Charles Dickens to break out of the three-decker novel paradigm and into cheaper, serialised newspaper fiction. Therefore, books were still largely the reserve of the upper classes, and often seen as a symbol of wealth for those of the rising middle classes. Of the 124 items in our collection that were printed in 1819, this display showcases just a few that help illustrate the above issues.

Ancient History, and especially Egyptology, was something of an obsession for Britons during the 19th Century, with Prichard’s An Analysis of the Egyptian Mythology, to Which is Subjoined a Critical Examination of the Remains of Egyptian Chronology being published in the midst of an emerging era of Egyptomania in the Western world. Napoleon’s failed Egypt campaign in 1798 and the country’s continued importance during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars led to a sort of arms race between Britain and France over Egyptian artefacts and scholarship. The United States was also majorly affected by an obsession with Egyptian history, with the Washington monument obelisk being the greatest example of this.

More recent history was also of great interest to consumers, whether domestically or from abroad. John Williams’ The history of the Gunpowder Treason: collected from approved authors, as well Popish as Protestant (WEG/M 20/OLD) is an examination of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 which targeted King James I and is now popularly celebrated on 5th November, or Guy Fawkes Day. This work is an 1819 reprint of an earlier work published in 1679 and therefore shows a relatively contemporary reaction to events.

However, as the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot only bolstered Protestant dominance in England in the 17th Century and led to even more severe anti-Catholic laws, it is sensible to assume that regardless of the title of this work, which references accounts from both Catholics and Protestants, it is probably a very biased account. It is very unlikely that an account originally published only 74 years after the event was actually a rigorous and even-handed examination of events. It would be extremely interesting to know whether 1819 audiences (and specifically Gladstone, who owned this book) were conscious of this issue and examined the events in a less biased manner.

International issues were also of concern, especially regarding globally famous figures such as Galileo Galilei and his dealings with the Catholic church. This pamphlet: The Accusation, Condemnation and Abjuration of Galileo Galilei, Before the Holy Inquisition, at Rome, 1633 (45/A/7), was written by various authors and published in 1819. By the 19th Century, science was comfortable with the ideas of Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo and Newton. It was widely accepted that the Earth, and all planetary bodies, revolved around the sun and that this was due to forces such as gravity. Of course, the Catholic church did not actually officially declare in favour of heliocentrism until 1822, however, by that point it was due to the necessity of public opinion and not because they were in anyway leading the charge. The publication of this sort of history, which critiqued the establishment and showed the persecution of free-thinkers, was a dangerous example according to the government as Britain was being rocked by political agitation and unrest during this period.

More and more publishers were being prosecuted when they published either un-approved texts or critical essays on the British government and establishment. The invention of the pamphlet was itself a political act as it made printed works more accessible to readers. A pamphlet was much more affordable to both print and buy than a fully bound book and so more people could have access to its contents. Richard Carlile was the publisher of this pamphlet and was famous as a political agitator and publisher whose business model relied on making radical works more available to the poor through the splitting of them into pamphlet sections. It was through this method that he made books by renowned thinker Thomas Paine more available and ended up spending time in prison when the government prosecuted him for blasphemy, blasphemous libel and sedition due to the publication of material that might encourage people to hate the government and criticise the Church of England.

Collections of essays were also very popular at the time as a way of gaining the maximum amount of information for the lowest price, at a greater convenience. In May’s display we have a number of copies of The British Essayist, a series of 45 volumes which each collected essays from the same or similar authors. One of the examples here is a collection of essays by Richard Steele and Joseph Addison – who were both prominent literary figures in the 19th Century. Steele was creator of The Tatler – a journal that cultivated essays on contemporary manners and which he later dissolved in order to start the Spectator journal with Addison. This 1711 publication of the Spectator is not connected to the modern journal, except in possibly supplying the name; the same is true regarding the modern Tatler and the eighteenth-century journal, The Tatler.

Also displayed is a fine example of book conservation with one of the British Essayist volumes having been rebound in the 20th Century, likely due to wear and weakness of the original nineteenth-century binding. When compared to the originally bound volumes placed next to it, we can see that the re-binding is very obvious – the alterations have clearly prioritised function over design. This is often true in a library environment when there are limited budgets and the use of books is prioritised over the look of them. Despite a newer binding, it is still important to take care when reading books like this, as in this case specifically, the manuscript is still 200 years old.

Thomas Busby’s A general history of music from the earliest times to the present, condensed from the works of Sir John Hawkins and Charles Burney (WEG/V 75/BUS) is an excellent example of the artistic marbling technique that can be seen adorning the page edges, boards and end papers of many Georgian and Victorian publications. The art of marbling was spread to Europe from the Middle East in the 17th Century when travellers bought examples of books adorned with the design style. It also became a popular handicraft for non-commercial book printers when Englishmen Charles Woolnough published his The Art of Marbling in 1853.

1819 was clearly an interesting year for the publication and reading of books. As Britain came to the end of the Regency, political agitation grew, and publishing was central to this. Increased access to the printed word through the collection of essays or publication of pamphlets was crucial in spreading political ideas that the establishment may not have approved of. Additionally, trends in academia such as ‘Egyptomania’ can be seen through the publication of books for both the academic and popular market. Despite the trend for cheaper and more mass-produced books, limited runs with expensive designs were still prevalent with techniques such as marbling and book jacket design meaning books weren’t just functional items but also art pieces.

The display is available for all members of the library to see in the display case in the History Room. Members of the public who wish to see the display and learn more about the library should join a ‘Glimpse’ at 12pm, 2pm, or 4pm, 7 days a week. This is a short tour wherein a library staff member will summarise the history of Gladstone and the Library before guiding guests through the Gladstone Foundation Collection.

For more information about the evolution of print culture in the 19th Century, click here.

Bibliography:

Busby, Thomas, A general history of music from the earliest times to the present, condensed from the works of Sir John Hawkins and Charles Burney (WEG/V 75/BUS)

Galilei, Galileo, The Accusation, Condemnation and Abjuration of Galileo Galilei, Before the Holy Inquisition, at Rome, 1633 (45/A/7)

Prichard, J.C., An Analysis of the Egyptian Mythology, to Which is Subjoined a Critical Examination of the Remains of Egyptian Chronology (K 20/11)

Steele, Richard, and Addison, Joseph, The Spectator in British Essayists [6-15], London: 1819 (R 16/2b)

Williams, John, The history of the Gunpowder Treason: collected from approved authors, as well Popish as Protestant (WEG/M 20/OLD)

By Sophie Hammond, Graduate Work Experience