LADY MARY GLYNNE (1786-1854): LETTERS HELD AT GLADSTONE’S LIBRARY

This is the second in a series of guest blog posts written by visitors to Gladstone’s Library. Researchers from all over the world come to the Library to work with our special collections and archives. The blog posts will highlight the fantastic resource our collections can be for researchers from a variety of disciplines, and we hope they inspire you to explore our collections in new ways. If you are considering a research project, please get in touch by emailing [email protected].

By Chris Fozzard, Chester-based teacher, local historian and writer

Gladstone’s Library holds a valuable collection of letters written to Lady Glynne after 1800 that I had the privilege of viewing whilst researching a society that met in Chester in this period [1]. I thought she may have been involved but it turned out to have been her sister-in-law, Anne. I was well into the correspondence when I made this discovery and resolved to complete my review of it regardless. The picture that emerged, brief highlights of which are set out here, made it more than worth the while.

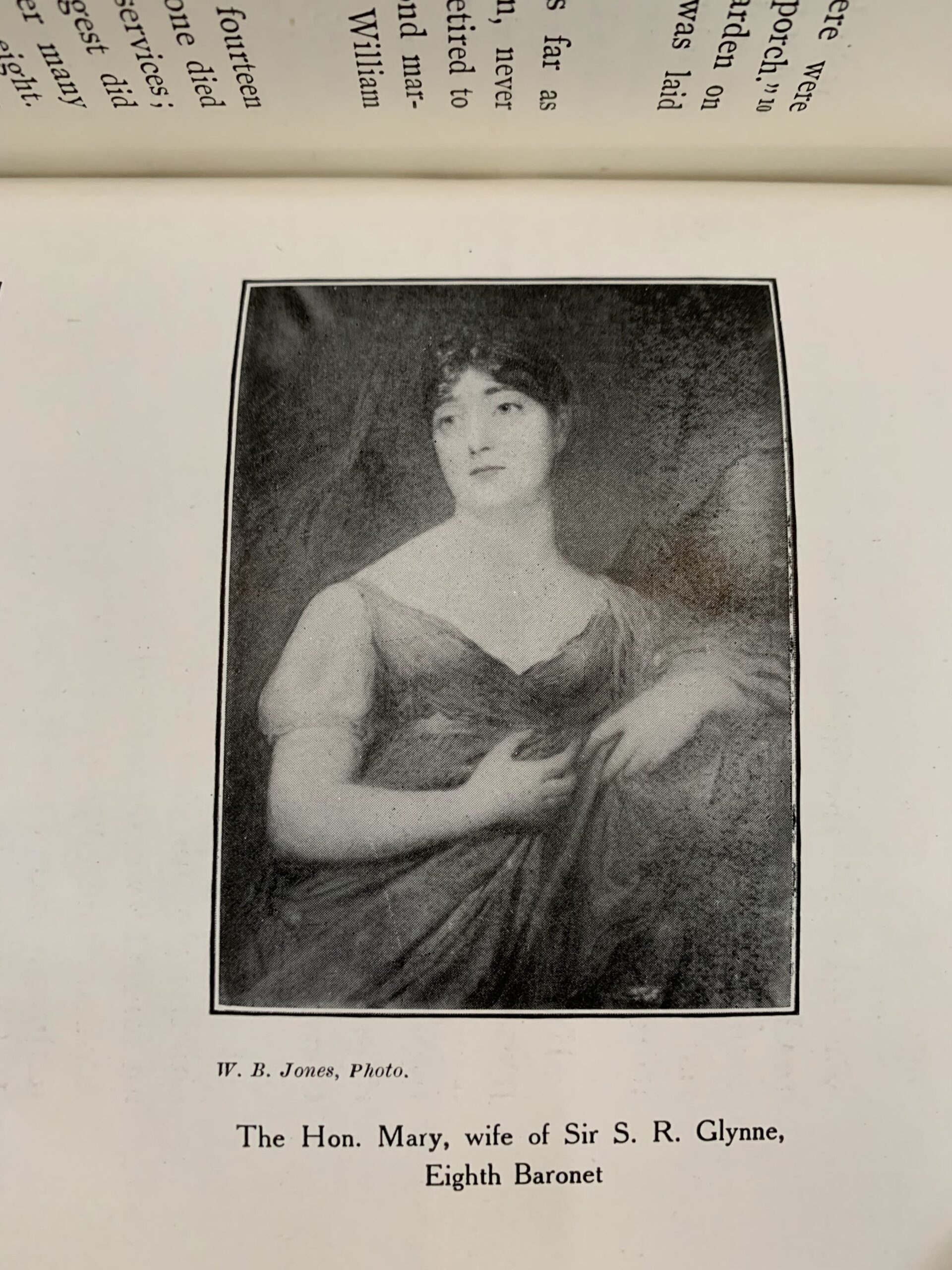

A portrait of Lady Mary Glynne

Lady Glynne was the daughter of Lord Braybrooke and distantly descended from Norman and Plantagenet kings. More recently, she was related to five British Prime Ministers, including the Grenvilles and the Pitts. She would become mother-in-law to a sixth: William Gladstone. In 1806 she married Sir Stephen Glynne, 8th Baronet of Hawarden, but their union was tragically short-lived. He died of consumption in Nice in 1815, leaving his wife with four young children. The most immediate problem for Lady Glynne was how to escape the Riviera as Napoleon reasserted control in France following his escape from Elba. A tortuous route through Italy, Switzerland and Flanders eventually brought her home to safety. A white charger that had been acquired from Napoleon after he rode it at the Battle of Borodino in 1812 was among the party. It lived on for several years before being buried on the Hawarden estate [2]. As a young widow, Lady Glynne devoted herself to her children, dividing her time between Hawarden, family properties in England and pieds-a-terre in France. Other important people in her life included her uncle Thomas Neville, her sister Caroline and her brother George. She had no shortage of admirers but, as a point of principle, declined the opportunity to remarry.

There was misfortune in her later life too. She suffered a stroke in 1834 from which she never fully recovered [3]. The letters reveal mounting financial pressures within the family, culminating in a crisis in the late 1840s following a speculative investment in ironworks, which led to the temporary abandonment of Hawarden and its ultimate conveyance to the Gladstones [4]. She spent much of her later life at Hagley Hall in Worcestershire – her daughter Mary’s marital home – where she would pass away at the age of 67.

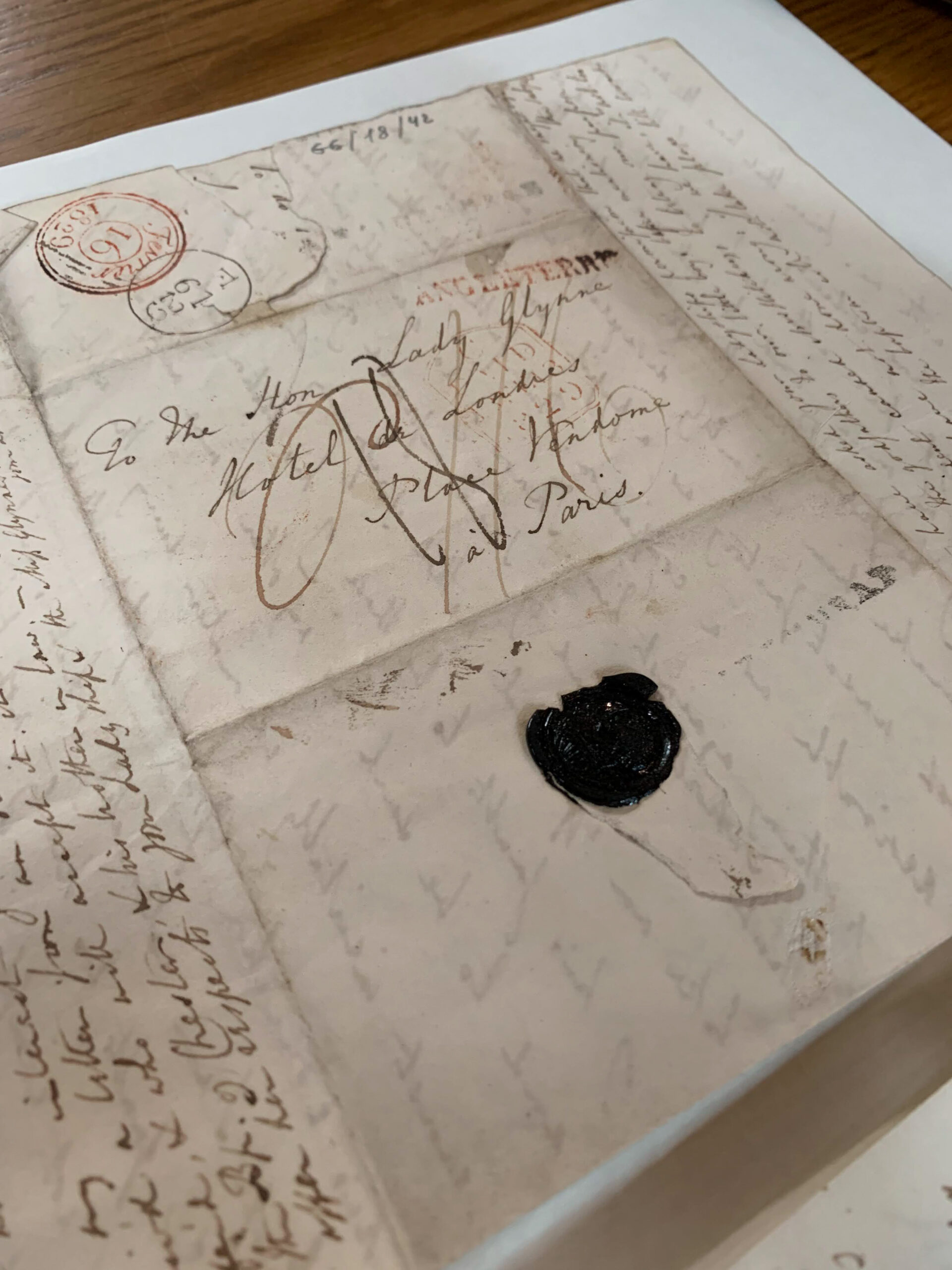

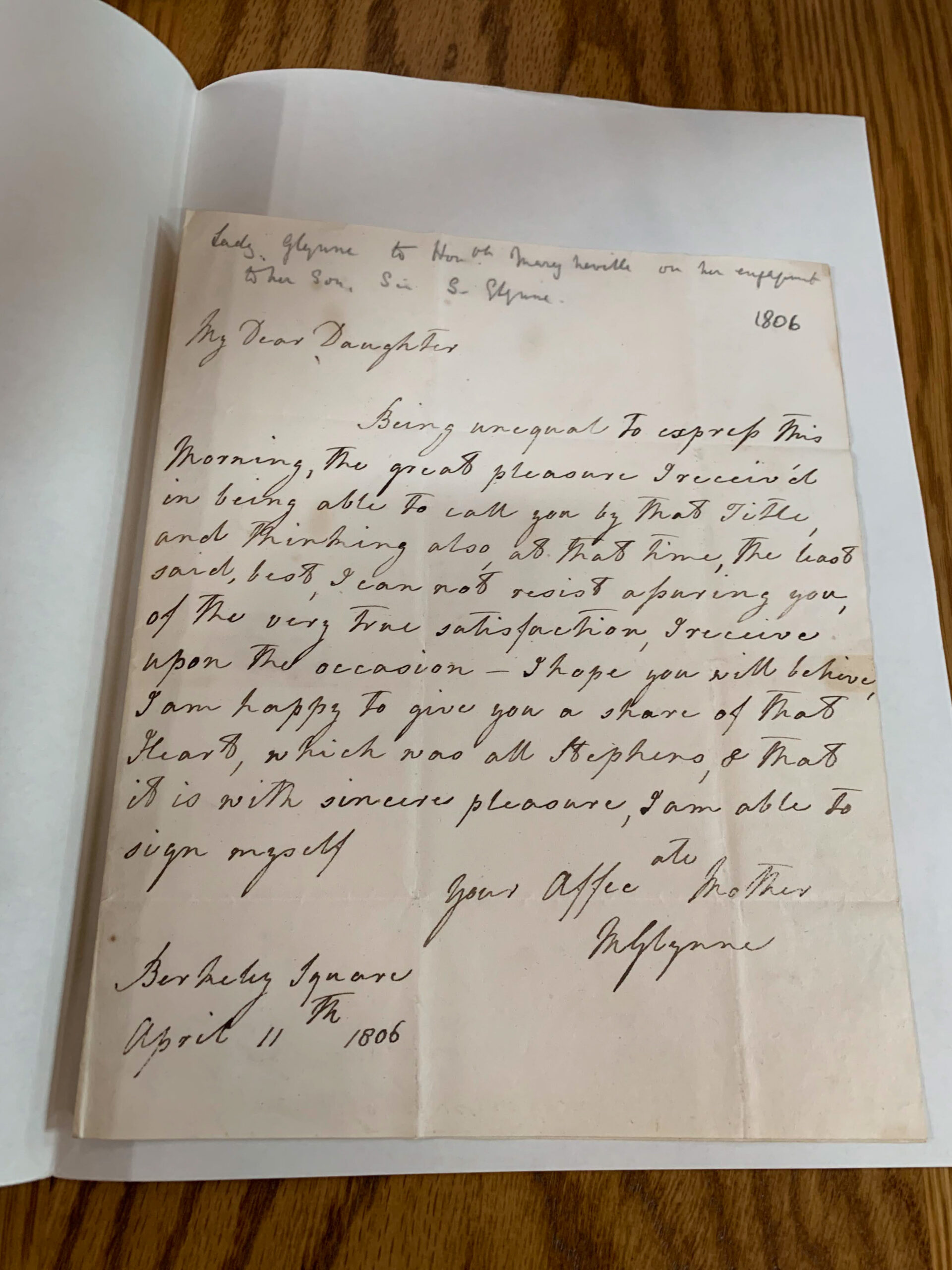

(L) An envelope of a letter to Lady Glynne and (R) a letter from Lady Glynne to her daughter in law

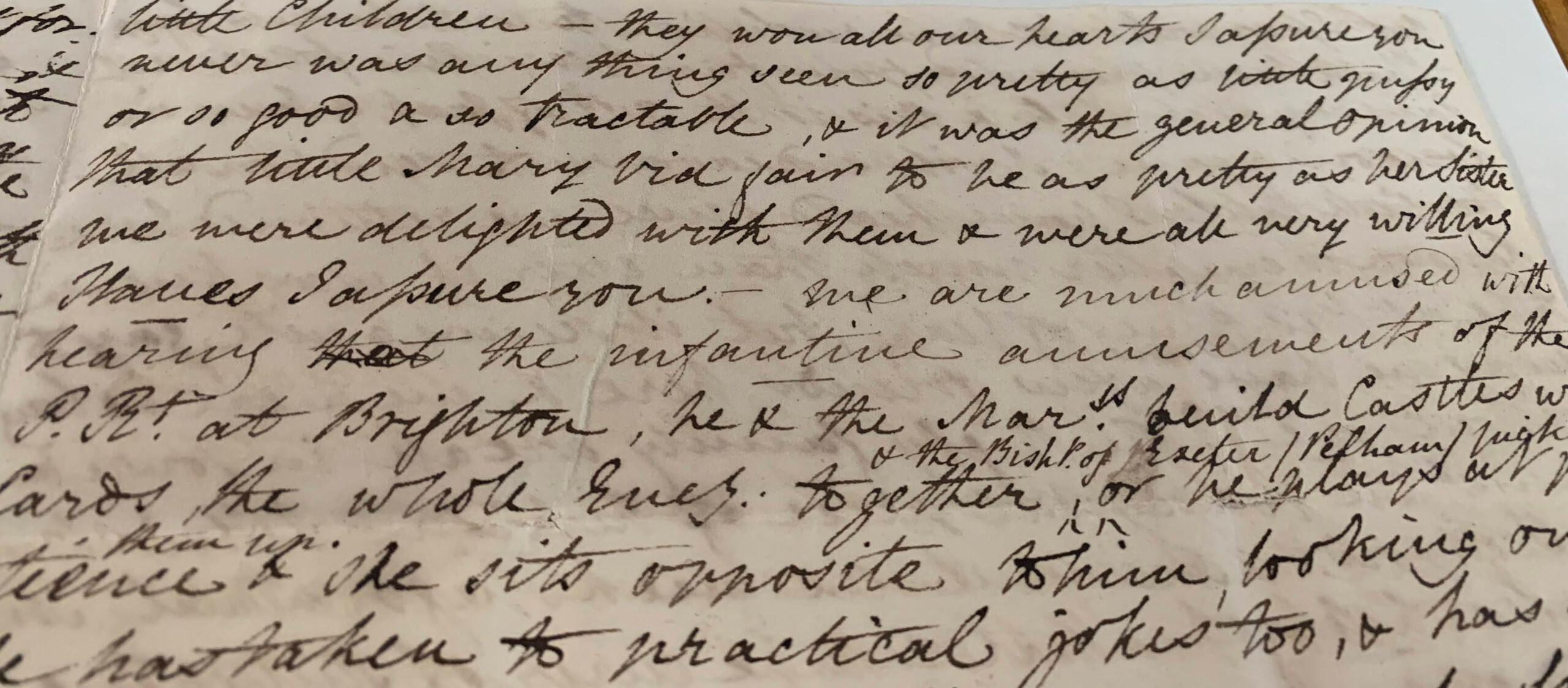

An early letter in the collection is from the dowager Lady Mary Glynne conveying effusive congratulations to the younger Mary on her engagement to her son in 1806. Soon the young children of that union become common topics of conversation. Lady Bradford, a regular correspondent, displays a particular intimacy with and affection for them. Letters sent to Lady Glynne as she nursed her husband in Nice express concern for him but otherwise are light and convivial in tone. For example, Anne Cornewall makes wry references to the Prince Regent’s ‘infantine behaviour at Brighton’, consorting with his mistress and playing practical jokes on his companions, including draping Admiral Sir Edmund Nagle in Lord Petersham’s clothes, ‘he being a remarkably small man’. She also provides, by her own admission, ‘tittle-tattle’ on their friend, Mr Beckford, who is suffering a long exile from his wife and family to pursue a much-vaunted cure for stuttering. The reporting of the episode closes with a fervent wish that he may be ‘rewarded for his Roman fortitude’. There are allusions too to ill-advised marriages and attempts to prevent or repudiate them, in the days long before divorce was legal.

Anne Cornewall’s comments on the Prince Regent

Lady Williams, whose children appear to be implicated in these marital misfortunes, makes no reference to them in her own contemporaneous letters to Lady Glynne. Instead, she addresses the Paris social scene, describing a mutual acquaintance there as ‘leading a more dissipated life than ever she did at the height of the London season’ and bemoaning the ‘extravagant expense of dress’, which was proving a constraint for many socialites. She goes on to express the hope that ‘your invalid does not find this weather as punishing as we do’. Continental conditions appear to have been excessively cold that January, perhaps hastening Sir Stephen’s death a few weeks later.

Marriages which feature happily and fulsomely in the correspondence include Lady Henriette Williams-Wynn’s to Thomas Cholmondeley, 1st Baron Delamere at Wynnstay in 1810, and George Neville’s to Charlotte Legge at Westminster in 1816. The Wynns and Cholmondeleys were close family friends of the Glynnes, and George Neville was Lady Glynne’s brother, long-time Rector of Hawarden and later Dean of Windsor. A rare letter in the collection from Lady Glynne features the first of these marriages. It seems to have been delayed due to an attack of rheumatism on the part of the bridegroom but was a grand affair when it eventually proceeded, concluding with an elaborate procession from Wynnstay to Vale Royal via Chester which very much excited the local populous.

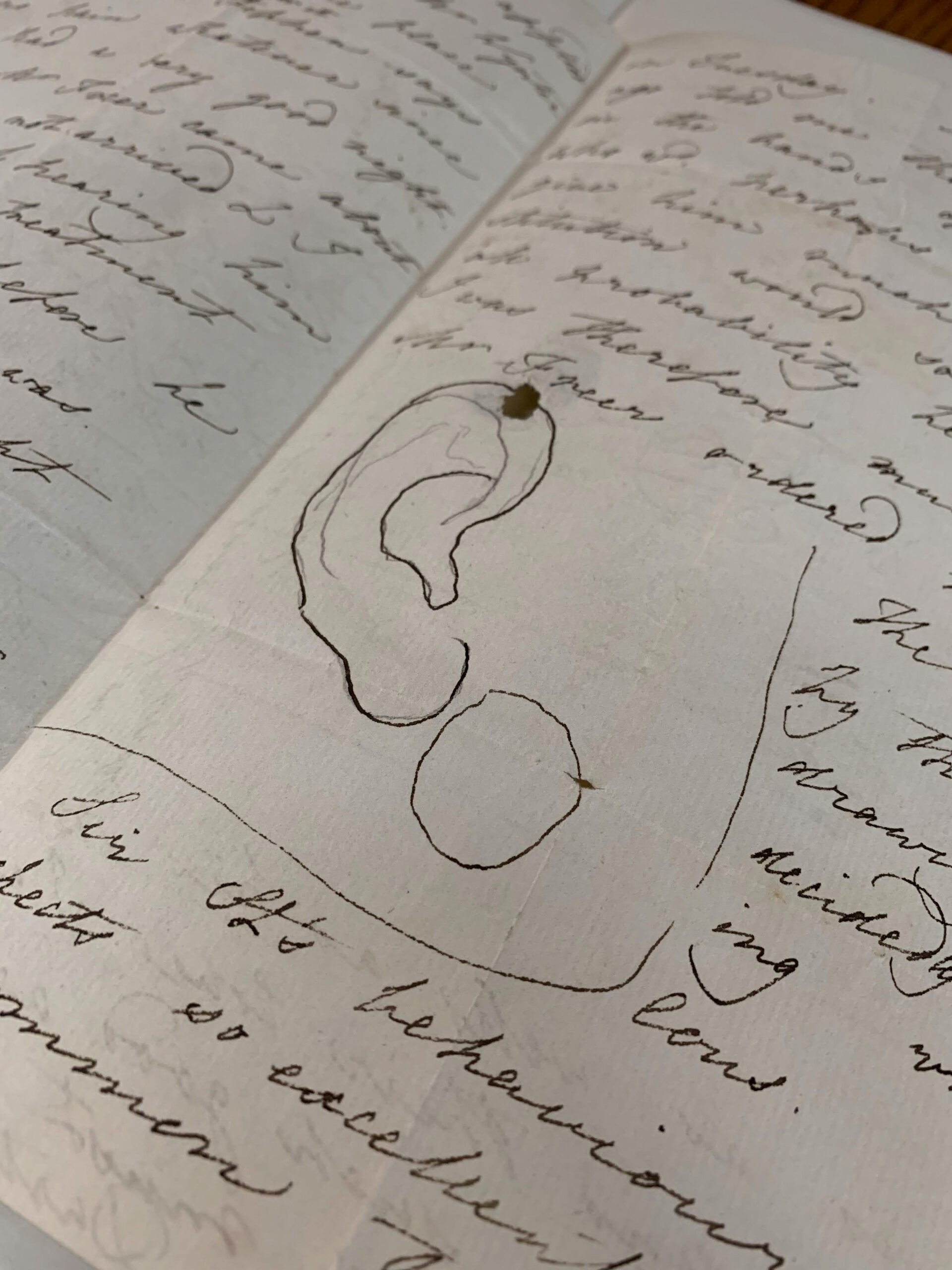

A sketch of Stephen Glynne’s injured ear – detailed below.

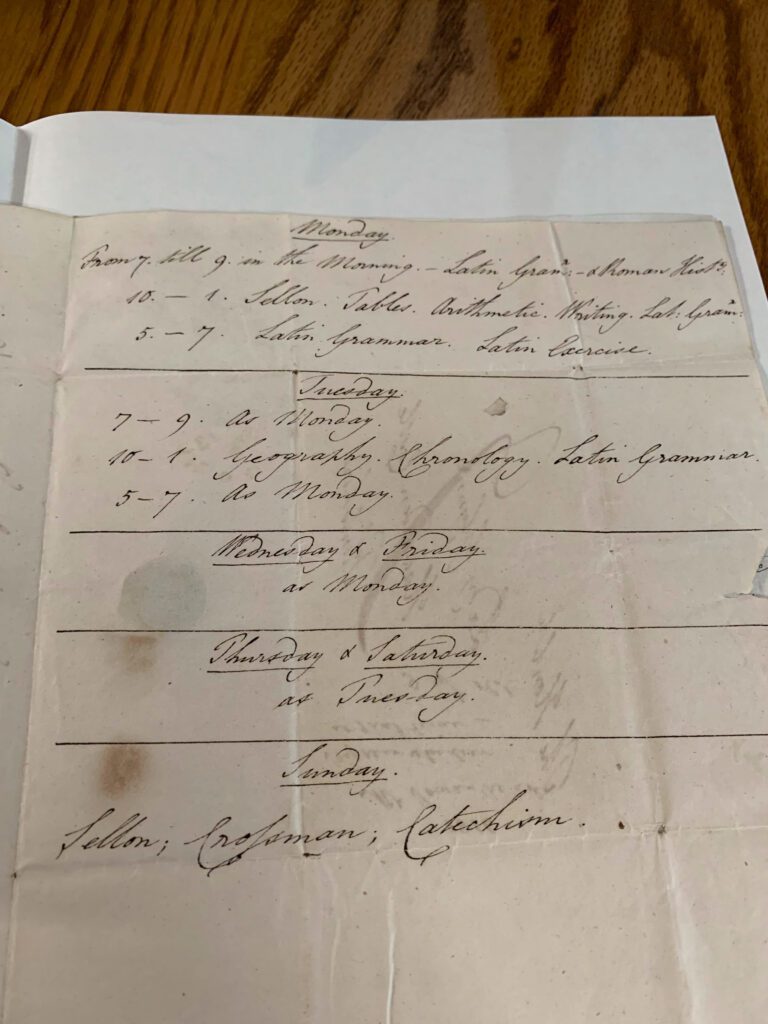

The education of the children is another running theme. There are letters from masters at Eton and Wargrave reporting on the progress and prospects of Stephen and Henry. There appears to have been some rivalry and even enmity between them, occasioned by Henry’s sense of inferiority academically, which the reports indicate was not misplaced. One early letter documents a physical encounter between them and includes a sketch of Stephen’s injured earlobe. Later correspondence covers their progression through Christ Church, Oxford, into politics and, in Henry’s case, entry into the ministry as a prelude to succeeding his Uncle George as Rector of Hawarden. There is also reference to Stephen’s coming of age celebrations in September 1828, which ran up a total bill of approximately £60,000 in modern day terms.

Letters from and about governesses abound in Catherine and Mary’s case. Lady Glynne places much emphasis on music and Italian, which she regards as necessary accomplishments for the young ladies. They are even taught piano by a precocious Franz List, the renowned composer, during one of their spells in Paris. The French capital becomes a more regular place of resort as the daughters approach their majority. Here they attend the best balls and mix in the highest society.

One close friend and eminent writer and scholar who achieved high ecclesiastical office was Reginald Heber, Bishop of Calcutta. A letter to Lady Glynne sent just before his departure for the post in 1823 expresses regret at the lack of opportunity for a final visit and thanks her for her ‘beautiful present’, which appears to be a personalised journal. This he promises to complete and display to her on his next visit to England, though this never happens due to his much-lamented early death in India in 1826. By all accounts, the connection between them ran deep and Lady Glynne’s sense of bereavement at this tragic event would have been keenly felt.

The correspondence thins out from 1830 onwards, particularly after Lady Glynne’s stroke. Her daughter Mary, now Lady Lyttleton, keeps in touch from Hagley when her mother isn’t there. She and her husband move in very exalted circles, including during a prolonged stay at Chatsworth in 1839, which she describes as ‘very pleasant but rather formal’. There are allusions at this time too to a financial squeeze, perhaps presaging the crisis that will rock the family a few years later. Mary writes that her mother-in-law ‘has left me so many directions about keeping accounts that I mean to follow exactly … if we can but make ends meet, we shall be the happiest people’. Elsewhere she states, ‘Poor Stephen dreaded very much going back to Harden [sic], he means to keep his accounts and conduct in a very regular manner.’ There are several undated letters from Mary in the collection too, though a good estimate of timing can be inferred from the contents of some. One mentions the near certainty of marriage between the Queen and Prince Albert of Coburg, whose engagement was announced in October 1839. Another confirms the marriage and expresses the wish that she might attend, which indeed she did, in the company of her sister.

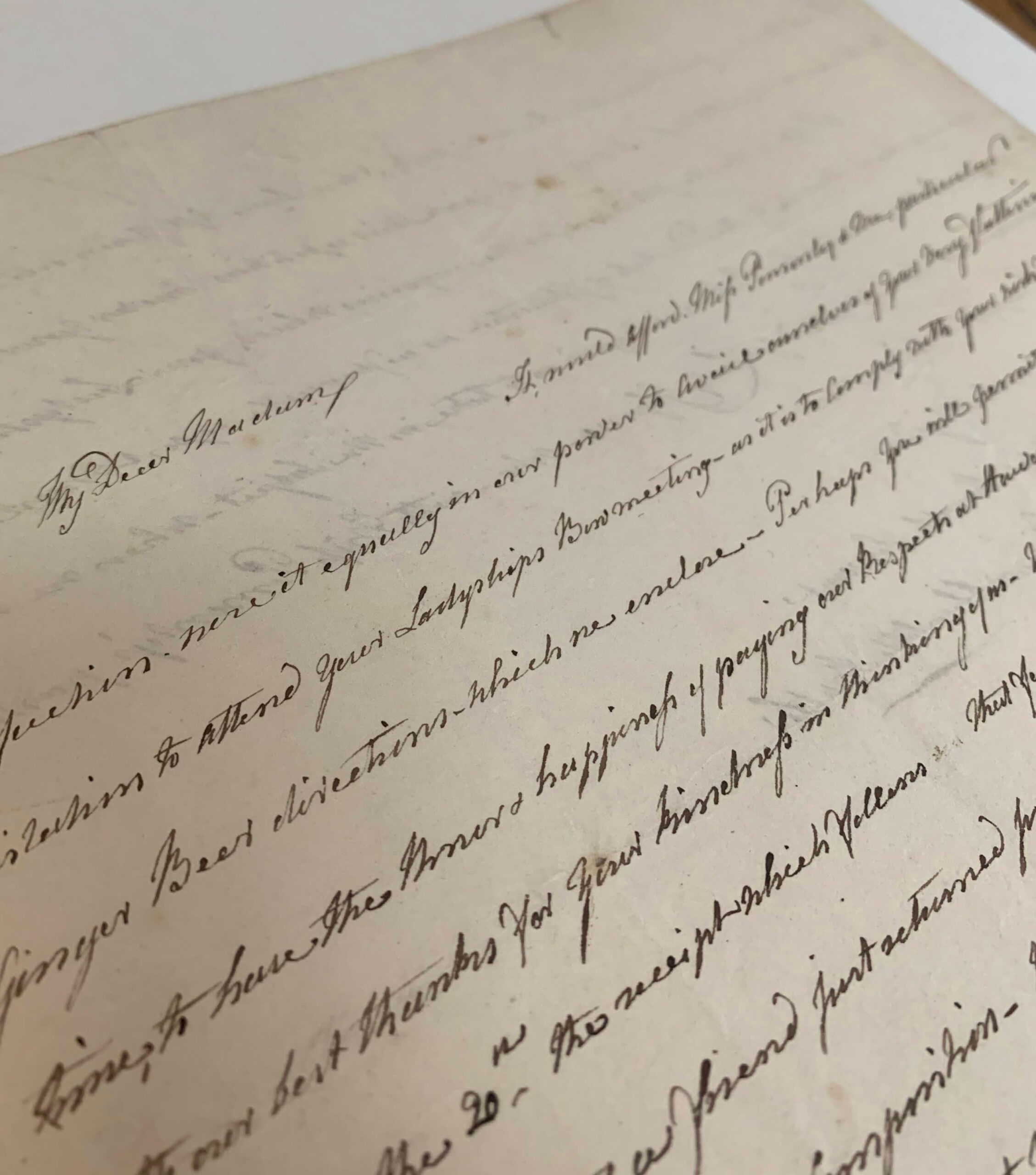

A letter from Eleanor Butler

Two further undated letters relate to the renowned Irish émigrés and boon companions, the Ladies of Llangollen, including one from Eleanor Butler herself. This appears to be declining an invitation to a bow meeting – archery being a popular pursuit – but requesting another opportunity to visit Hawarden at ‘some quieter time’ and enclosing an exclusive recipe for ginger beer. The second is from a Mrs Kenah, wife of Colonel Kenah, and is entitled ‘Substance of a conversation with the Ladies of Llangollen’. The couple had been invited to Plas Newydd, home of the ladies, and offered breakfast, dinner and supper and ‘you’ (the colonel’s wife) the carved room, ‘but the colonel must out at night for we never lodge gentlemen’. Mrs Kenah continues: ‘We had a tender parting and the colonel paid me his respects the following day and brought me a little chained keepsake from Llangollen.’ She thanks Lady Glynne for a lengthy stay at Hawarden too, suggesting a stronger relationship than a solitary letter implies.

References

[1] Correspondence of Lady Mary Glynne née Neville (1787-1854), Ref GG/18

[2] Drew, M., Catherine Gladstone (Nisbet & Co, 1919)

[3] Hilderley, J., Mrs Catherine Gladstone: ‘A Woman Not Quite of Her Time’ (The Alpha Press, 2014)

[4] Jenkins, R., Gladstone (Pan Macmillan, 2002)