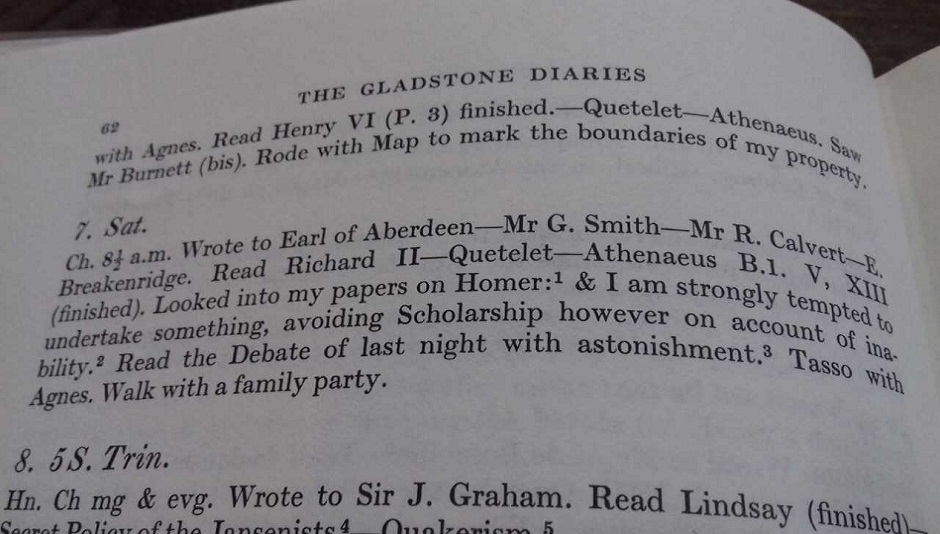

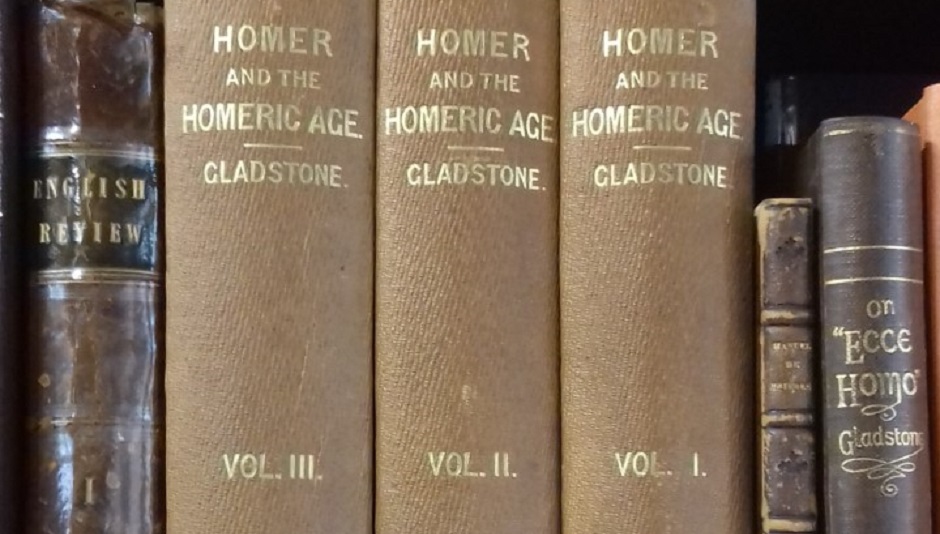

‘Looked into my papers on Homer: & I am strongly tempted to undertake something…’ wrote Gladstone on 7th July 1855, unaware that that ‘something’ would occupy his thoughts for much of the next three years. What began as a small project to be completed while out of office grew to a three volume work: Homer and the Homeric Age (1858).

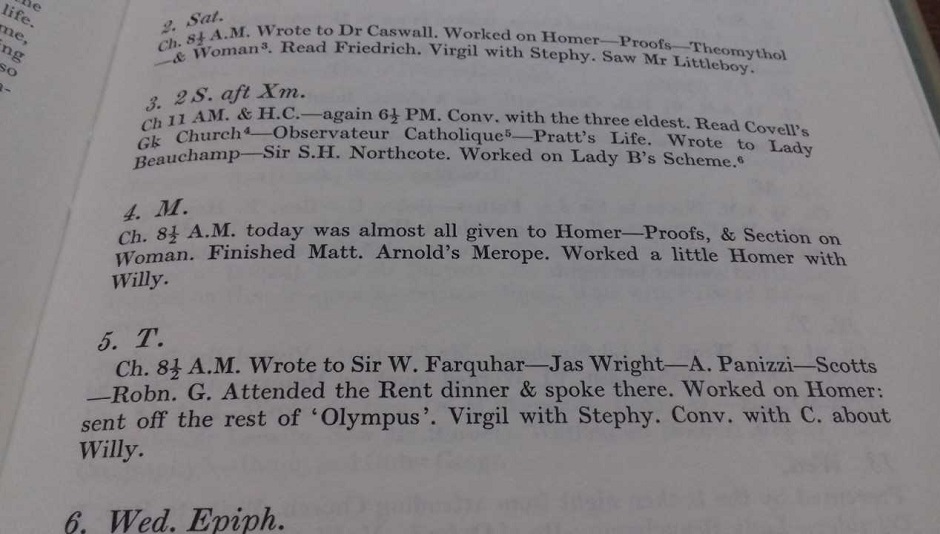

During this period Gladstone arguably spent more time with the dead than the living. His diaries show that he read passages from the Iliad and the Odyssey almost every day, and he often refers to Homer as ‘Old Homer’, as if addressing a close friend.

It is not really surprising that Gladstone developed an interest in Classics. The Eton and Oxford educated politician was introduced to Latin and Greek at a young age; but Gladstone’s passion for the subject went unusually far beyond that of his peers, and he was often mocked for his interest. Indeed it would appear that Gladstone’s obsession with Homer was a source of contention, and he never achieved the literary success that his rival, Benjamin Disraeli, enjoyed.

Aldous’ The Lion and the Unicorn reveals some of the most scathing remarks made by Gladstone’s contemporaries about his classical scholarship. Lord Tennyson dubbed Homer and the Homeric Age “hobby-horsical”, and Lord Acton wrote an exasperated letter to his wife bemoaning “a dreadful hour” he had spent listening to Gladstone wax lyrical about Homer. Even Benjamin Jowett, Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, had strong words to express: “It’s a mere nonsense”, he wrote (p.97-8).

In Homer and the Homeric Age Gladstone extolls the virtues of Homer’s epic poems and criticises those who did not fully appreciate him as a man who was in his opinion, “…the greatest chronicler that ever lived” (p.290). Oxford University, he complained, only employed Homer ornamentally while he was a student there. It did not occur to them that Homer was worth serious study. Clearly Oxford, and much of parliament, were of the same mind.

Yet Gladstone remained indifferent to mockery and relentlessly pursued his interest. He published numerous works on classical subjects, including Juventus Mundi (1869), which was written while he was in office as Prime Minister for the first time. He was immensely enthusiastic about Homer and his world, and nothing would have deterred him from writing about the poet. “His [Homer’s] place among the greatest poets of the world”, Gladstone wrote, “whom no one supposes to be more than three or four in number, has never been questioned.” He continued to dismiss all opinions to the contrary, despite strong opposition. In his mind Homer had been a great man: a supporter of religion and greatly appreciated by many – backed by the theory that his epics had survived due to their superior quality. He saw Homer’s work as something to be valued, and wanted his contemporaries to see that too.

We may ask: Why did Homer fascinate Gladstone so much? The most likely explanation, as Bebbington suggests in The Mind of Homer, is that he found his studies cathartic – a distraction from a busy political career. From 1855 to 1858 he dedicated most of his time to Homer and happily left parliament alone. Closeted away in his study at Hawarden Castle, he poured his energy into his writing, and if we are to believe his son-in-law, Edward Wickham, this is what gave Gladstone the most pleasure. As Wickham wrote: “His heart was more in his books and in the questions of theology and philosophy which stirred him deeply.” (pp. 2-3).

By Susannah Burtinshaw, Intern

Correction: This piece was amended on 9th January 2022 to give the full quotation from Edward Wickham’s reflections on Gladstone, and to add the reference to the bibliography.

Bibliography

Aldous, R. ‘The Lion and the Unicorn’ (2006)

Bebbington, D. ‘The Mind of Gladstone’ (2004)

Gladstone, W.E. ‘Homer and the Homeric Age’ (1858)

Gladstone, W.E. ‘Juventus Mundi’ (1869)

Jenkins, R. ‘Gladstone’ (1995)

Matthew, H.C.G. ‘The Gladstone Diaries, 1855-1860’ (1978)

Wickham, E. C., ‘Mr Gladstone as seen from near at hand’, Good Words (Jul. 1898)