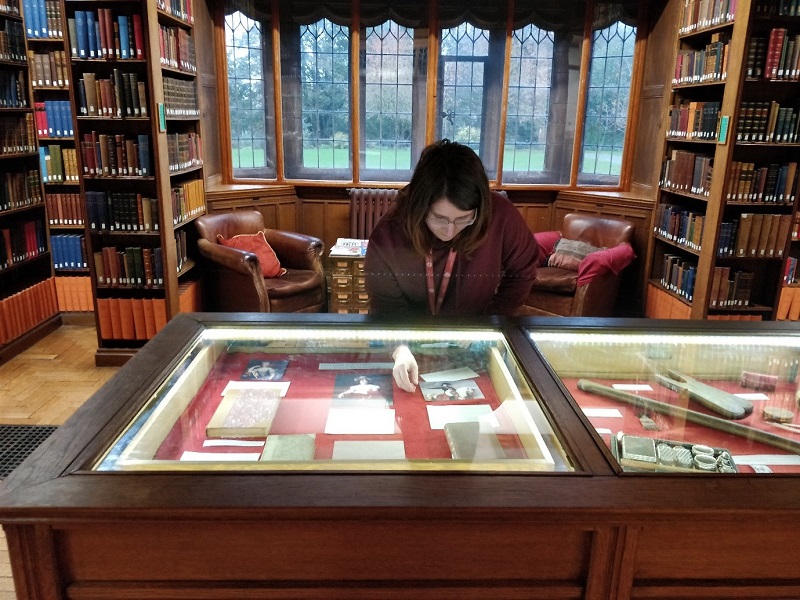

Every month the library team curates a new display for visitors and everyone who uses the library, highlighting the many wonderful collections we have on our shelves. This month, Intern Elspeth Brodie-Browne has put together an exhibit on one of the great figures of the French Revolutionary period, who died 200 years ago…

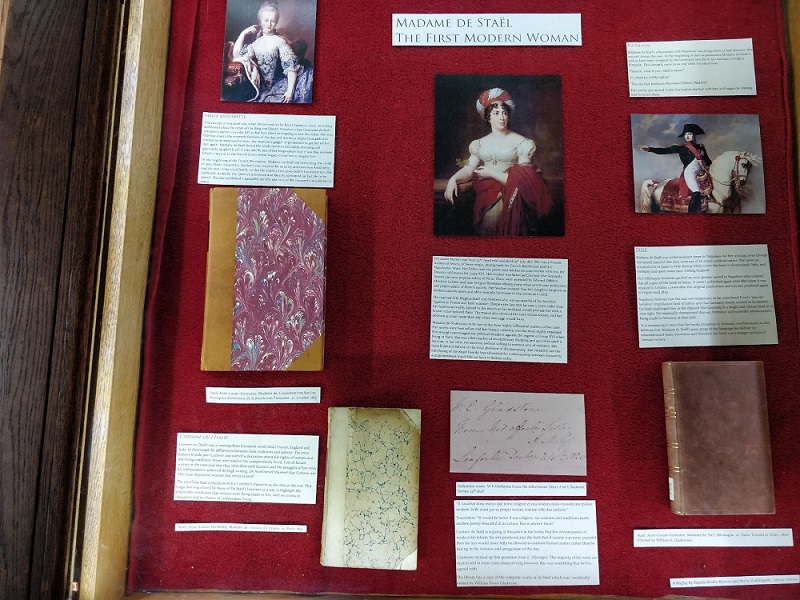

Literature, just like everything else, has trends and fashions and sadly Madame de Stael (born 22nd April 1766 and died 14th July 1817) has fallen out of vogue, despite being one of the most well-known and influential female writers during her lifetime. I am ashamed to say that I myself had not paid any attention to de Stael before being tasked with creating a display about her life for the History Room as part of my internship at Gladstone’s Library.

Exiled from France for her novels being too political; a feud with Napoleon; an order to burn her books; a friend of Rousseau; falling on her face in front of Marie Antoinette and the rest of the French Court (this is not metaphorical, she literally tripped when bending down to kiss the robes of the French monarchs and required a ‘gaggle’ of gentleman to bring her back to her feet) – Madame de Stael lead a fascinating, and at times scandalous, life against the back-drop of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars.

Never one to shy away from the struggles that faced her sex, she tackled them in both her fictional and non-fictional writings. Her literary heroines who strived to break free of the constraints placed on them by society came to tragic ends. Madame de Stael drew particular attention to the lack of access to education that women endured; de Stael herself had a very thorough and well-rounded education thanks to the insistence of her Mother. Her explosive book L’ Allemagne (this was the one that enraged Napoleon so much he ordered that all the copies be burnt!) dedicates an entire section to examining ‘The German Woman’ and her role in society.

Germaine de Stael was that rare thing in French society, a woman who was desired and sought after, whose appearance was nothing spectacular. In fact it was barely ever mentioned! Her friends and acquaintances made a great deal of her captivating eyes but they were the only physical features that received praise. It was her wit, intelligence and lively conversation that drew people to her. It might have been this failure to fulfil the ornamental purpose of a woman that lead our very own Lord Byron to claim she ’would have made a wonderful man’.

Well, no offence to Lord Byron, but I think she made a wonderful woman.

Hopefully the display Sheila and I have put together about the ‘First Modern Woman’ will restore her to her rightful place in the minds of those who see it.

Elspeth Brodie-Browne, Intern