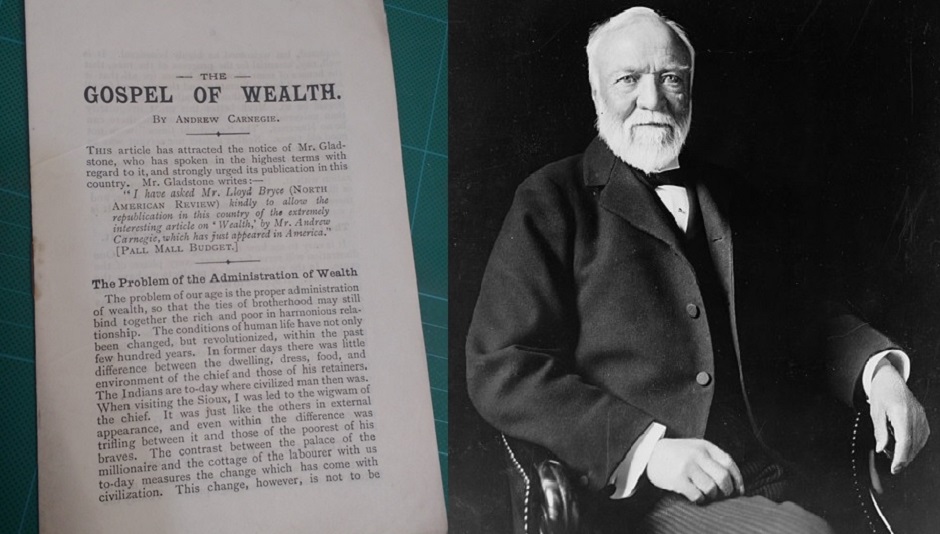

[Image: Left – Gladstone’s Library; Right – Andrew Carnegie by Theodore Christopher Marceau (Public domain)]

Many of our patrons will know that in January 2018, the Library embarked on a three-year project externally funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York under the title of Digital Gladstone. The project aims to fully digitise and catalogue 15,000 nineteenth-century manuscript letters and 5,390 annotated printed books. These images will then be hosted online allowing free-access to readers all over the world, making Gladstone’s legacy more accessible than ever before. However, what most may not know is that William Ewart Gladstone’s relationship with Carnegie is much more far reaching than this one project; in fact, Gladstone was very good friends with the great philanthropist, Andrew Carnegie himself.

Andrew Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland where his father was involved in the local Chartist movement. When the movement went into decline in 1848, the family sold their belongings to book passage to America for themselves and their sons, 13-year-old Andrew and five-year-old Tom. From an early age, Andrew Carnegie acted to improve his own life through hard-work and education. At the age of 14 he was hired as an errand boy by a local telegraph company, where he taught himself how to use the equipment and was promoted to telegraph operator. He was superintendent by the age of 24 and then began to invest in railways and steel, from which he would make his multi-million-dollar fortune. Throughout his life he emphasised the value of education and self-improvement through the use of public libraries. Indeed, much of Carnegie’s early success relied on the knowledge he gained through access to the private library of Colonel James Anderson, who opened his collection up to local men and boys to give them options for self-improvement [1].

‘It was from my own early experience that I decided there was no use to which money could be applied so productive… as the founding of a public library.’

– Andrew Carnegie [2]

In 1901, Carnegie sold his steel company for $303,450,000 and became the richest man in America. However, he was not content just to live the rest of his life in the lap of luxury, and in fact was eager to get rid of his great wealth in his lifetime through philanthropic efforts. By 1911, he had created five charitable organisations in the USA and three in the UK but was becoming tired of the burden of philanthropic decision making. To ease this burden, and on the advice of a friend, Carnegie established the Carnegie Corporation of New York in 1911 ‘to promote the advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding’ through grant making. [3] He transferred the bulk of his remaining $150 million fortune to this organisation to distribute, and entrusted it to a board of trustees who continue to have control of the Corporation today [4].

In 1889, Carnegie wrote his article, ‘Wealth’, for the North American Review. The article is now more commonly known as ‘The Gospel of Wealth’ due to a change of title when it was published in Britain. The article outlines the responsibilities of new self-made millionaires in tackling wealth inequality.

‘…rich men should be thankful for one inestimable boon. They have it in their power during their lives to busy themselves in organizing benefactions from which the masses of their fellows will derive lasting advantage, and thus dignify their own lives.’ [5]

Carnegie argues that the wealthy should utilise their surplus riches to reduce the gulf between the rich and poor, in contrast to traditional patrimony, where wealth is instead handed down to heirs. He argues against extravagance, irresponsible spending, and self-indulgence, instead promoting philanthropy and the welfare and happiness of others. In many ways, Carnegie’s article has been incredibly influential; the actions of modern billionaires such as Bill and Melinda Gates, Warren Buffett and Mark Zuckerberg, in committing to ‘The Giving Pledge’, which states that they will voluntarily give away the majority of their wealth to philanthropic causes, has its roots in Carnegie’s philosophy [6].

‘The Gospel of Wealth’ became famous in Britain when British Prime Minister William Gladstone helped to organise its publication in the Pall Mall Gazette. Carnegie and Gladstone became well-acquainted through the Earl of Rosebery, and the politician and biographer, John Morley, who were friends and colleagues of both. [7] There was a great respect between the two titans: Andrew Carnegie once called Gladstone ‘the world’s greatest citizen’ while Gladstone once called Andrew Carnegie an ‘example’ for the wealthy [8].

‘To Gladstone Carnegie was ever the embodiment of that ‘enlightened personal benevolence’ he put so much store in as a counter-manifestation to the modern movement of political ideas and forces.’ [9]

Despite this great personal respect, and Gladstone’s championing of Carnegie’s article being published in the UK, he was not wholly in agreement with Carnegie’s viewpoint. Gladstone’s review of the article was positive but tempered, as he defended primogeniture, unlimited inheritance, and the British Aristocracy. Because of this, many other British critics denounced Carnegie’s ‘radical’ philanthropic ways, which led the American to publish a series of articles clarifying and defending his viewpoint [10]. He clarified that he did not advocate for free handouts from the upper class to the poorer, but instead to ‘help those who help themselves…[and ] provides[sic] part of the means by which those who desire to improve may do so’ [11].

Despite disagreements between the two on ‘The Gospel of Wealth’ Gladstone was not too proud to ask the other man for funding when he felt there was a deserving cause. Carnegie once recalled that on one day alone, he had letters from John Morley, Herbert Spencer, and William Gladstone (all titans of British politics at the time), and the latter two were both asking for funding (for the Bodleian Library in Gladstone’s case).

‘”Just think,” Carnegie wrote in reply to Gladstone, “one mail brought me three letters. One from you—Gladstone…One from Herbert Spencer…One from John Morley…I am quite set up as no other one can say this. A.C.”’ [12]

Despite his amusement at his philanthropic fame, Carnegie still refused both Spencer and Gladstone. Regarding the Bodleian, he was already endowing a large library in Pennsylvania at the same time, that he deemed a more urgent project. It is clear that despite being, as Mark Twain called him, ‘Saint Andrew’, [13] he was not a soft touch even for his friends.

To learn more about Andrew Carnegie, and to hear him read his ‘Gospel of Wealth’ article, click here.

Bibliography

Butler-Bowdon, Tom, 50 PROSPERITY CLASSICS: Attract it, Create it, Manage It, Share It – Wisdom from the best books on wealth creation and abundance (Nicholas Brealey Publishing, 2009) quoted in City Wire, Book Review: The Gospel of Wealth by Andrew Carnegie (25/01/09) [https://citywire.co.uk/funds-insider/news/book-review-the-gospel-of-wealth-by-andrew-carnegie/a327029] (Accessed 19/03/19)

Carnegie, A, The Gospel of Wealth, North American Review (June 1889). Reprinted in The Annals of America, vol. 11, 1884–1894 (Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1968), 222–226 [http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5767] (Accessed 24/03/2019)

Carnegie Corporation of New York, Andrew Carnegie’s Story [https://www.carnegie.org/interactives/foundersstory/] (Accessed 19/03/19)

Devadason, Rajen, Carnegie and the gospel of wealth, New Straits Times (20/09/15) [https://www.nst.com.my/news/2015/09/carnegie-and-gospel-wealth] (Accessed 19/03/19)

Frazier Wall, Joseph, Andrew Carnegie (Oxford University Press, 1970)

Nasaw, D, Andrew Carnegie (Penguin, 2007)

Penguin Random House Canada, The Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie and the Gospel of Wealth [https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/299468/the-autobiography-of-andrew-carnegie-and-the-gospel-of-wealth-by-andrew-carnegie/9780451530387] (Accessed 19/03/19)

Shannon, R, Gladstone: 1865-1898 (UNC Press Books, 1999)

References

[1] Carnegie Corporation of New York, Andrew Carnegie’s Story [https://www.carnegie.org/interactives/foundersstory/] (Accessed 19/03/19)

[2] Carnegie Corporation of New York, Andrew Carnegie’s Story: Industrious Youth [https://www.carnegie.org/interactives/foundersstory/] (Accessed 19/03/19)

[3] Carnegie Corporation of New York, Andrew Carnegie’s Story: Giving and Legacy [https://www.carnegie.org/interactives/foundersstory/] (Accessed 19/03/19)

[4] Carnegie Corporation of New York, Andrew Carnegie’s Story [https://www.carnegie.org/interactives/foundersstory/] (Accessed 19/03/19)

[6]Butler-Bowdon, Tom, 50 PROSPERITY CLASSICS: Attract it, Create it, Manage It, Share It – Wisdom from the best books on wealth creation and abundance (Nicholas Brealey Publishing, 2009) quoted in City Wire, Book Review: The Gospel of Wealth by Andrew Carnegie (25/01/09) [https://citywire.co.uk/funds-insider/news/book-review-the-gospel-of-wealth-by-andrew-carnegie/a327029] (Accessed 19/03/19)

[7] Nasaw, D, Andrew Carnegie (Penguin, 2007), p.239

[8] Penguin Random House Canada, The Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie and the Gospel of Wealth [https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/299468/the-autobiography-of-andrew-carnegie-and-the-gospel-of-wealth-by-andrew-carnegie/9780451530387] (Accessed 19/03/19)

[9] Shannon, R, Gladstone: 1865-1898 (UNC Press Books, 1999), p. 482

[10] Nasaw, D, Andrew Carnegie (Penguin, 2007), pp.351-4

[11] Carnegie, A, The Gospel of Wealth, North American Review (June 1889). Reprinted in The Annals of America, vol. 11, 1884–1894 (Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1968), 222–226 [http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5767] (Accessed 24/03/2019)

[12] Frazier Wall, Joseph, Andrew Carnegie (Oxford University Press, 1970), p. 825

[13] Penguin Random House Canada, The Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie and the Gospel of Wealth [https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/299468/the-autobiography-of-andrew-carnegie-and-the-gospel-of-wealth-by-andrew-carnegie/9780451530387] (Accessed 19/03/19)

By Sophie Hammond