We are very lucky here at Gladstone’s Library to have access to around 130,000 printed items in total, including around 6,500 books printed before 1800 and some as early as the 15th Century. The majority of these older books come from a very small proportion of our collections: either our pre-18th Century collection, the Bishop Moorman Franciscan collection, or the Glynne-Gladstone collection. Many of these older books are kept in our Closed Access rooms in order to keep them in the best condition possible – but as a result, regular visitors to the library might not be aware of what treasures lie behind closed doors!

Today, we will be looking at fragmentary manuscripts used in bookbinding. Leaves and parts of parchment leaves have been used in bindings of manuscripts since the Middle Ages. The use of manuscript fragments in bindings increased greatly at the end of the 15th Century when printed books began to appear in increasing numbers, supplanting many older manuscripts. Furthermore, the conversion of northern Europe to Protestantism and the closing of monasteries and convents resulted in the discarding of many Catholic religious and liturgical manuscripts some of which were used by bookbinders. The fragments are commonly found in printed books from the 15th to the 17th centuries, used in a variety of ways such as wrappers or covers for the book, as endpapers, or cut into pieces and used to reinforce the binding.

Here at Gladstone’s, a delve into our Closed Access section unearths many treasures and delights!

|

|

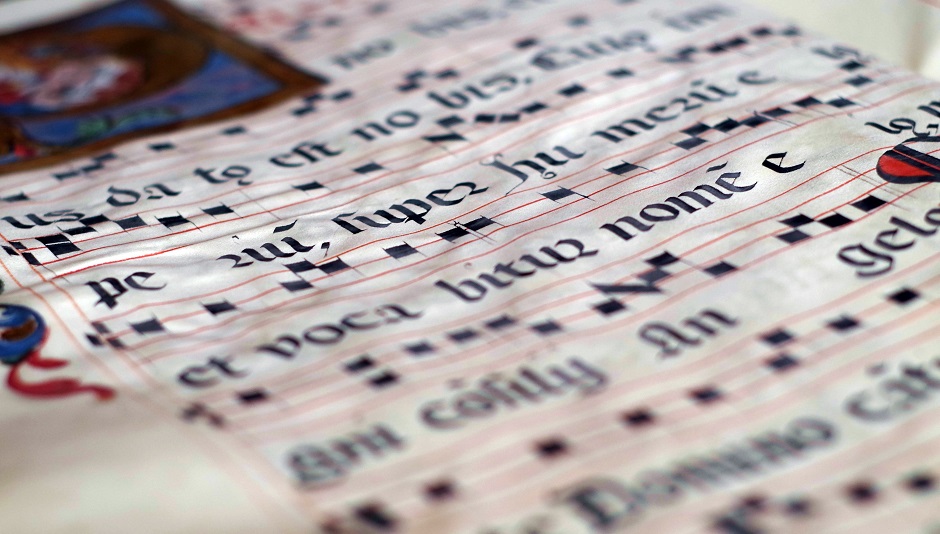

MOORMAN F.C./804 – Chant binding. Saint Bonaventura, Opuscula & tractatus quamplurimi Sancti Bonaventure Cardinalis ordinis minoru, 1497

The music shown in the fragment above is most likely Gregorian Chant, a form of unaccompanied sacred song of the western Roman Catholic church. Each note was sung by every member of the group chanting, hence each note being the same length, and Gregorian chant has no meter so could be sung at whatever speed was preferable – hence the lack of bar lines! The shape of the notes reflected whether they were being sung in ascending order (square) or descending (diamond), and notes on top of each other indicated that the bottom note was sung first.

This particular find is a delight because it covers the whole book! The book itself is only the size of an A5 piece of paper, meaning the music is written quite large and may have been used as a copy to hold up for the choir to see during practices. It is likely that the original cover of the book was lost, and that it was rebound with this ‘waste’ manuscript! The book itself is an incunabule, or a book printed before 1500 – these are relatively rarer than later printed books, with this particular book printed in 1497.

|

|

MOORMAN F.C./1218 – flyleaf. Fratres Tertii Ordinis Sancti Francisci, Forma investiendi, circa 1400

This ‘book’ is actually not a book at all, but a manuscript bound together by vellum! Dating from around 1400, it is one of the oldest manuscripts in the library, and features an element of manuscript inception! The original manuscript has been bookended by two flyleafs, both of a different manuscript, with a dedication to the ‘Fratres Tertii Ordinis Sanctis Francisci’ written on the inside. There is also an annotation at the back of the bound collection, featuring what looks like a sketch of some Gregorian Chant music with the Latin written underneath!

HIL D.I 33 – printed spine fragment. Robert Willis, Principles of mechanism: designed for the use of students in the universities and for engineering students generally, 1841

This printed fragment shows that it wasn’t just handwritten manuscripts that were being used to bind books! This book was itself published in 1841, which is a little later than our other fragment-bound books, but shows that fragments were used to reinforce book bindings for a while after printing became more commonplace. You may even be able to read some of the writing of the fragment – it looks like it may be from an article reviewing books.

|

|

MOORMAN F.C. 969. Ubertino da Casale, Arbor vite crucifixe Jesu denotissimi fratris Ubertini de Casali ordinis minorum, 1485

Finally, our most impressive example, and another incunabule! This book shows a range of manuscript fragments in use, including both flyleafs and reinforcing strips across the spine and cover. Both manuscripts are most likely in Latin, and the larger page is likely to be on a theological topic. You can also see that the two manuscripts used are different from one another, and were likely taken from some scrap manuscript the binder had nearby! Both of these types of manuscript fragments are fairly commonly found in books printed between 1450 and 1650, although it is unusual for both of them to be so clearly visible.

The large flyleaf has a small amount of silver leaf on the starting letters of each line – this is an unusual finding, as manuscripts donated for scrap weren’t usually finished to such a level, and gives the manuscript the rather lofty title of being ‘illuminated’!

Fragmentology, or the study of manuscript fragments, is an ongoing process! A number of online projects have been started to collect images of these and other manuscript leaves in a virtual reconstruction of the original manuscripts, and this has been referred to as ‘digital fragmentology’. Websites have also been used to identify and date manuscript fragments through crowdsourcing.

As you can see, there is some real variety in the appearance of manuscript fragments found in books printed from 1450 to 1650 (and beyond!) Hopefully this blog has introduced you to some of the treasures of Gladstone’s Library, and some of the treasures that can be found in old books – just with a little digging!

By Amy Cooper, Graduate Work Experience