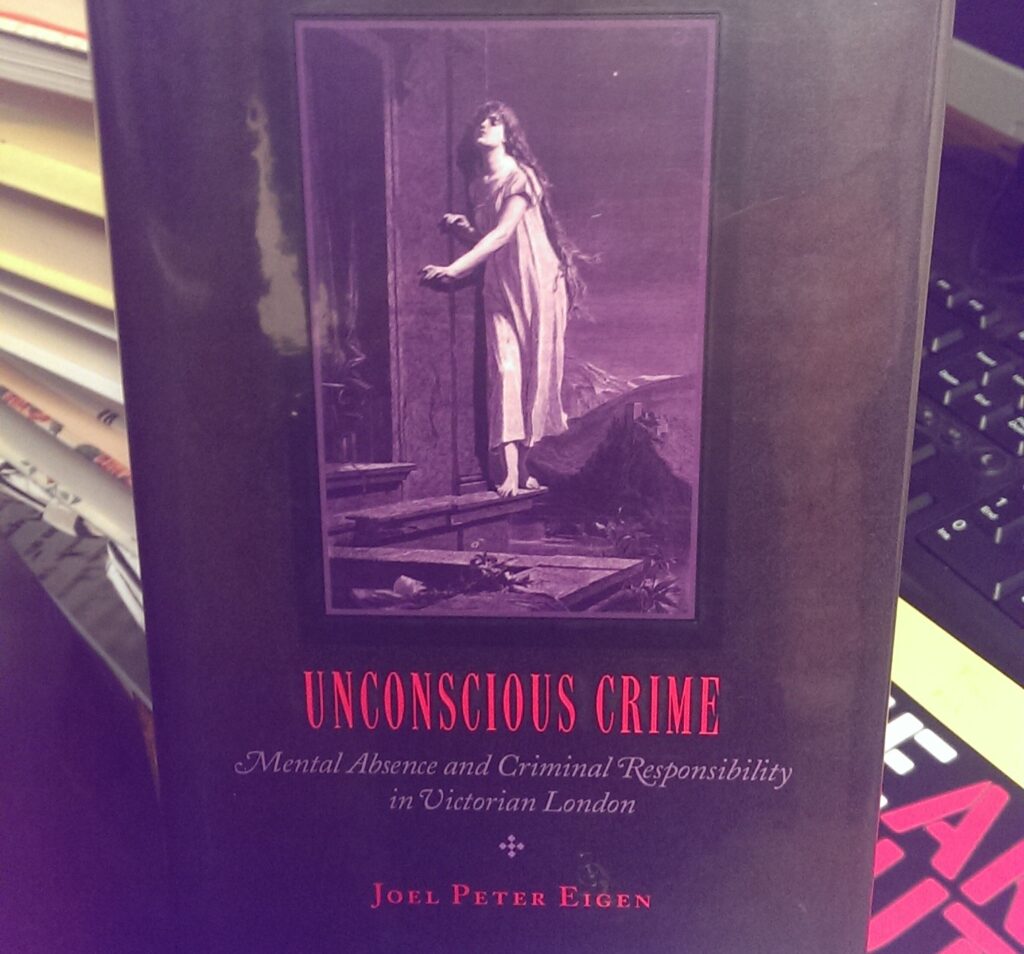

Unconscious Crime: Mental Absence and Criminal Responsibility in Victorian London by Joel Peter Eigen, which can be found in the Annex at Gladstone’s Library.

By Joshua Zeoli

In the chapter titled ‘Double Consciousness in the Nineteenth Century’. Eigen explores the impact on how multiple personality disorders supposedly jeopardised the criminal justice system through the nineteenth century. Eigen also draws upon early cases in which mental health was used as a defence plea.

It was not until the eighteenth century, when legislation was created which saw the criminal justice system detain those who were considered to insane at the time of the offence. The Criminal Lunatics Act (1800) could be seen as one of the earliest pieces of legislation where the offender would be punished for their crimes. However Eigen notes that since 1760 there had been a functioning role for the “mad doctor” in court cases dealing with offenders pleading that they were insane.

This chapter also tries to offer definitions of how multiple personality disorders were defined in this particular era. They were defined as “delusional people who were seen with an altered persona”. The first persona was seen as reserved and inhibited, while the second, which was also known as the alter-ego was seen to be animated and vivacious. Eigen suggest that these terms were problematic and vague, due to their being a limited knowledge on personality disorders at the time.

Eigen highlights that this was problematic as it was often difficult for medical doctors to determine whether someone was insane at the time of the offence, if they were not currently having a manic episode at the time of the trial. He later builds up evidence on suggesting that medical witnesses were reluctant to entertain the possibility of blind impulse and impaired self control. This highlights the idea that there was a reluctance to label individuals as insane.

Eigen also refers to Dr. Hess a defence witness who reinforces the point that it was increasingly difficult to assess whether an individual was suffering delusions from a mental illness. He argued that those who suffered from dream related hallucinations caused serious questions to be asked involving criminal responsibility, which could pave way to a better system equipped to dealing with insanity.

However this chapter also looks at the reasons against incarcerating those who are seen to be suffering from delusions. John Locke (1690) argued that “To punish someone in their sleep, is no more right than punishing a twin for his sibling’s action.” This brought into question about whether it was morally acceptable for the offender to be prosecuted for a crime that they had no control over. It can be seen that Eigen offer examples as to why there were moral dilemmas when dealing with these cases.

Overall Eigen provides a compelling insight into how the criminal justice system dealt with those who were supposedly seen as insane. This chapter would be considered an excellent starting point for those who want to gain an insight into how the Victorian criminal justice system responded to those who pleaded insane.

Want to know more about Victorian Crime? Josh, a Criminology and Scociology student at the University of Chester, has compiled this reading list. All texts can be found at Gladstone’s Library:

-

The Victorian Underworld : How the Victorians revelled in death and detection and created modern crime : Victoria’s Other London (Chapter 1) U37.8/85

This particular chapter explores Henry Mayhew’s findings on proletariat crime and how their morals seem to have developed into criminality. For example in the lower social classes prostitution was seen as a gateway to marriage.

-

The invention of murder: Science, technology and the law. (Chapter7) U40/24

This book reports on the different type of crimes, which were created or posed a copious threat to Victorian life. This particular chapter focuses on garrotting on board a fist class carriage, which caused the upper classes to consider the idea that nowhere was seen to be safe from crime.

-

Prison life in Victorian England. U37.8/82

This book looks at the different types of prisons and the legislation which was put into place during the Victorian era, including the 1865 Prison Act where “The jail and houses of correction were formerly merged into an institution called prison”. There was also the 1877 Prisons Act which caused local prisons to be taken over by the state.

-

Unconscious crime: Mental absence and criminal responsibility in Victorian London. U37.80

Examines the perpetrators who are seen to suffer from mental illness. It provides an interesting insight into how the criminal justice system dealt with those who were considered insane.

-

Fagin’s children; criminal children in Victoria England. U37.8/66

Looks at the types of crimes children committed and how they were punished. It also documented what it was like for children in prison.

-

Crime and punishment in England: A sourcebook U37.8/31

There is a specific entry on the many types of punishment a person could receive for garrotting.

-

Crime & society in England 1750 -1900. U37.8/33

Interesting parts on acts trying to deal with career criminals. The law officially recognised this by naming these types of criminals in the 1869 act as habitual criminals.

-

Crime and the Law U37.8/34

The book mentions the Gladstone report, which focused on the idea of restorative justice. For example Gladstone acknowledged that labelling the prisoner as criminals for the rest of their lives was not helpful as they were more likely to return back to crime.

-

Crime and insanity in England. U12/105 A&B

Discusses how insanity was an ineffective defence plea against a criminal charge, until the beginning of the 18th century, it explores how those who were seen to be mentally unwell were placed in the Gaols and bridewells.

-

The seven curses of London: Criminal suppression and punishment (chapter 10) U37/112 Looks at the way Lord Romily trying to suppress deviancy in juveniles. The book also mentions how career criminals should have their children taken away in order for them not follow in their parents footsteps.