In the late 1880s William Gladstone began the main project of his retirement; the transfer of about half his collection from his home in Hawarden Castle to a purpose built, corrogated-iron library on a purchased site in the village of Hawarden itself.

The first residential guest arrived shortly after, staying in what was then the Library’s ‘hostel’ – a separate house very close to the Library building. In 1898, following Gladstone’s death, work began on a grand new building, designed to bring together books and residents. It is this building that stands today.

Today, the Library is a completely independent charity (Registered Charity Number: 701399). The Gladstone’s Library charity owns the grounds and fabric of the Library and aims to maintain Gladstone’s legacy of engagement with social, moral and spiritual questions, helping people reflect more deeply on issues and ideas that concern them. It receives no government assistance and relies on income from bedroom bookings, restaurant bookings in Food for Thought, grants and donations from kind supporters to continue in its mission to protect this Grade I listed building and make its collections and study spaces accessible free of charge.

‘Be happy with what you have and are, be generous with both, and you won’t have to hunt for happiness.’

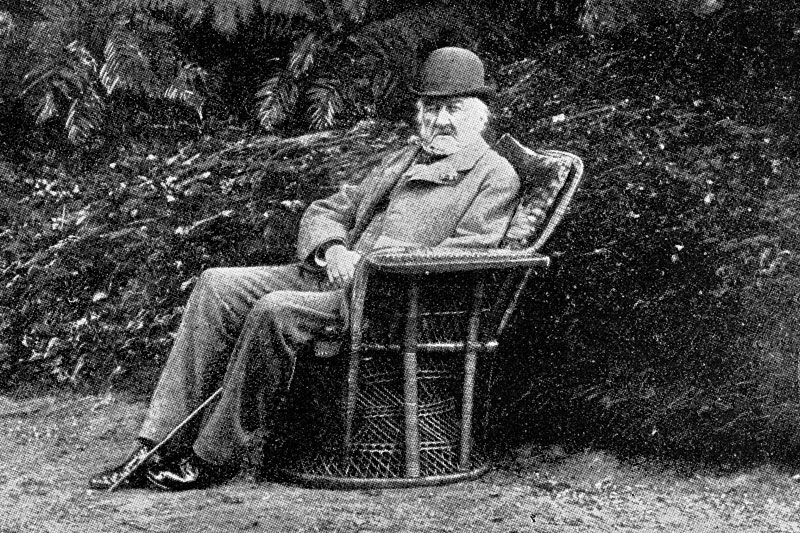

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone one of Britain’s longest-serving Parliamentarians, in a career that spanned both major political parties and several spells as Chancellor. His four times as Prime Minister is a record that still stands.

In his early political career, he campaigned for compensation for the owners of enslaved people, including his own father, John Gladstone, who owned substantial plantation ownings in Guyana, and advocated for gradual rather than immediate abolition. Later in life, he referred to the abolition of slavery as one of the greatest achievements of that century and was quoted as saying that enslavement was ‘the foulest crime that taints the history of mankind’ (Hansard, 19 March 1850).

The Library, which Gladstone was eventually to give to the nation, was entirely his own creation. Its formation began when, as a young boy – the son of a wealthy Liverpool merchant and benefactor – he was presented with a copy of Sacred Dramas by its author, Hannah More. Books acquired at Eton followed and the collection really began to grow during his university years at Christ Church, Oxford where he achieved a double first in Classics and Mathematics with another first in History, one of his passions.

His habit of annotating books continued throughout his life, as did his enthusiastic book collecting. His diary records regular searches of bookshops and book catalogues, and the reading of books in his study at Hawarden Castle, a room created upon Gladstone’s marriage to Catherine Glynne and his move to her family’s estate. Gladstone’s study functioned as a workspace, meeting-place, and library, and Gladstone would spend many hours a day there when at Hawarden. The study would become known as ‘The Temple of Peace’ to family, friends and the public; penny postcards could be purchased showing ‘Mr Gladstone at work’ in this book-lined room.

In his later years, Gladstone began to think about making his personal library accessible to others. His daughter, Mary Drew, would later write of her father’s intentions at this time: ‘Often pondering how to bring together readers who had no books and books who had no readers, gradually the thought evolved itself in his mind into a plan for the permanent disposal of his library. A country home for the purposes of study and research, for the pursuit of divine learning, a centre of religious life.’ (Mary Drew, ‘Mr. Gladstone’s Library at “St. Deiniol’s Hawarden”’, Nineteenth Century, 1906)

William Gladstone saw that the books classified as divinity and humanity would be of great value to members of all Christian denominations, but he also wished students from other faiths, or none, to have equal access to them. Such potential readers needed a place where they could stay and read with time to think and write in a scholarly environment.

The first step towards fulfilling this vision was taken in 1889 when a large corrogated-iron building was erected, containing two large rooms with six or seven smaller rooms to act as studies. This building became known as the ‘Tin Tabernacle’ or ‘Iron Library’, while the Library itself was named ‘St Deiniol’s’. Gladstone, by now over eighty years old, was closely involved in the transfer approximately 12,000 of his books from Hawarden Castle to their new home a quarter of a mile away, undertaking much of the manual labour himself, helped only by his valet and one of his daughters. “What man”, he wrote, “who really loves his books delegates to any other human being, as long as there is breath in his body, the office of introducing them into their homes?” (William Gladstone, On Books and the Housing of Them, 1890).

Once St Deiniol’s Library was established, Gladstone not only discussed his hopes with his family and with the trustees appointed to care for the Library and its books but in his will, he endowed the library with £40,000. This was more than a hobby or a sideline: outside of his children, this was his most major bequest. It’s clear that Gladstone fully intended his library to endure into the future, continuing to respond to issues of the day via its collections.

The Library was always envisioned as having a residential aspect, but at first the books were housed separately from residents. The ‘Tin Tabernacle’ stood at the back of the Reading Rooms – where the newer Annex stands now.

Following the death of William Gladstone in 1898, a public appeal was launched for funds to provide a permanent building to house the collection and to replace the temporary structure. The £9,000 raised provided an imposing building, designed by John Douglas, which was officially opened by Earl Spencer on October 14th, 1902, as the National Memorial to W. E. Gladstone.

This new building, which still stands now, was far more substantial than the ‘Tin Tabernacle’; it is a neo-Gothic Victorian design constructed of red sandstone (a familiar material in the area as there were sandstone quarries in Cheshire). The distinctive green slate used on the roof was likely quarried in Windemere.

In 1905, James Cape Story, a regular user of the Library, described it as ‘a temple of learning… a place for restful meditation, for research, for mental and spiritual refreshment and stimulus – and this amid charming natural surroundings, at the feet of the Welsh mountains’.

The Gladstone family funded the residential wing which welcomed its first resident on June 29th, 1906, and which was dedicated by A.G. Edwards, Bishop of St. Asaph on January 3rd, 1907. Residents and books were now under one roof. The Annex was added in the mid-twentieth century, while the Chapel and Glynne Room extension came in the early 2000s.

The Library continues to acquire books specialising in those subjects that were of most interest to Gladstone. There are now over 150,000 volumes in the main collection, reflecting Gladstone’s main interests (politics, history, theology and literature). As well as the ever-changing main collection, there are many special collections that contain some of the Library’s oldest and rarest books and manuscripts. The Library also has significant archive holdings, including the Glynne-Gladstone Archive.

For some time in the mid-twentieth century, the Library was a destination for clergy-in-training and relatively closed to the outside world – and for much of the Library’s history, a would-be guest had to present two letters of recommendation from members of the clergy to gain access. In the past thirty years the Library’s evolved to become far more inclusive, introducing a programme of open events and going through a series of refurbishments to improve the guest experience. Today, this remarkable institution remains a haven in which writers, students, researchers, bibliophiles, clergy and laity of all denominations can work or rest.

If you’d like to explore some of the ways you can financially support the work we do here at Gladstone’s Library, please click here.